Creating a working syllabus is hard. Where do you start? What comes next? How do you know when you’re ready to move on to the next thing? I find it helps to remember that there is no one correct answer, because the optimum structure for the syllabus depends on its goals, and the specific aptitudes and experience of the student.

The latest instalment of my Rapier workbook series (Rapier Part Two: Completing the Basics) contains the following technical content:

- Plate 8: voiding the front leg

- Plate 9: passing to attack (off-hand forwards)

- Plate 10: dealing with cuts to the head

- Plate 11: voiding low, and acting in contratempo

- Plate 17: voiding with the front foot

- Plate 18: passing to attack (off-hand back)

- Plate 19: voiding with the waist

- Capoferro’s three tempi (half, full, and one-and-a-half)

- Changing direction

That is a lot of material, and hard to remember, so I used the structure of the Rapier Footwork Form to organise it. This way, by the end of this book, you will have a series of actions clearly stuck in your head, which will act as an aide-memoire for all the plates that you know (including everything in the previous book: plates 7, 13 and 16). By running through the Form at the beginning of every training session, you will cover every major action in the system, and be reminded of the areas where you are strongest, and those that need most work.

You can see the form here:

I have also included some essential repetition from the previous book, notably the discussion on safety, and advice on how to use the book, because I know from experience that some readers will ignore “you need to read part one first”, and those things must be read before training.

Some people just want to learn how to sword fight. Others want to learn how to do the academic research side of historical swordsmanship. And some want to do both. These workbooks are obviously directed towards the “just teach me to sword fight” crowd, but I encourage all my students (and that includes you!) to at least be familiar with the primary source for your art, in this case, Gran Simulacro.

So what is form? and what it is for? Fundamentally, form is the mechanism we use for creating a narrative of the system within the students’ brains. You can think of a form as a string of pearls. In the beginning, each pearl is just one technique or action. It’s a tiny little seed pearl. But with practise, and a broadening understanding of the Art, each pearl becomes the locus for other concepts and actions to be stored. A single action acts as a trigger for a cascade of related actions. Form is therefore a set of chapter headings, under which you can store everything you ever learn about swordsmanship with the rapier; and once you have filled out each chapter, you have an index to your entire knowledge base.

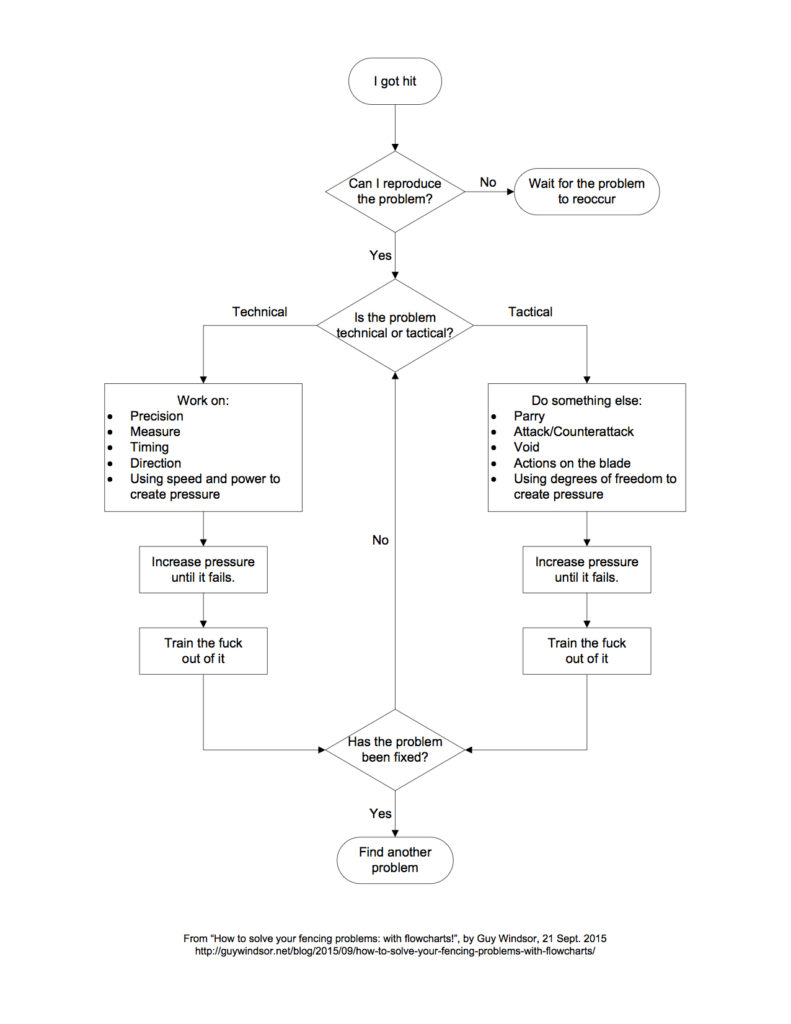

I cannot state this too strongly: the Form is just the beginning. It is not the be-all and end-all. When you write your own chapters, it becomes The Book of your rapier knowledge and skill. Once that is established you can simply run through the Form at any time and identify the weakest link. Start working on that link, using the “attached” training material, then re-run the Form to see whether what you have been working on is still the weakest link. The Form is therefore a diagnostic tool, an aide-memoire, a mechanics exercise or a guide to the system; in fact, it is the core of your practice. This workbook is about writing those chapter headings, and then filling in those chapters.

The major pitfall of this approach is that the organisation of the material in the Form has more to do with training space constraints and what felt good when designing it (“where do I want to go from here?”) than it does with any overtly logical structure. It does not, for example, follow the order of the plates in Gran Simulacro. Nor is it arranged according to difficulty. You may find yourself wanting to re-arrange things. That’s fine: the structure is (as with all forms) at least partly arbitrary. You only need to have this canonically correct if you are following my school’s syllabus and intending to grade within it. Otherwise, take this and make it your own!

When I was a kid, I spent some time casting little lead soldiers. It was magic: you heat up the lead in a pan until it melts, pour it into the mould and wait for it to cool down, and out comes a cavalry officer, rifleman or whatever. We then had to trim off the inevitable little leaks and the rather large riser (the extra bit where you pour the metal in, called a “sprue” in the US). Then the figures were ready for painting. You can think of the Form in a similar way. The actions of the person doing the Form are moulded by the actions of the (imaginary or real) opponents, as well as by the overall training goals. As with the casting process, there are artefacts to be taken into account: little bits of metal that don’t really belong, or some turns or steps that you wouldn’t normally use but are necessary to keep the Form in the right shape. So long as you know what the Art should look like and what the applications are, or what a Royal Horse Guards trooper from 1815 is supposed to look like, the Form is useful. As soon as the mould (your understanding of which actions do what) gets sloppy, the Form becomes a shapeless, pointless mess.

So here is a rule to be followed whenever you think about any kind of Form:

Application first, Form second.

We do this in class. When teaching the Form to students, we absolutely always do pair-drill (or handling drill) first, then the same actions solo, and then we add it to the Form. We never, ever, have students practising actions that they don’t know at least one application for, and we distinguish very clearly between a play or technique and a handling drill or skill-development exercise.

This post is an adapted extract from the new workbook. You can find the whole book here.

Or if you prefer learning from video classes, you should try my free Rapier Beginner's Class mini-course.

If you find the ideas here interesting, you may also like this post:

The Dragon: how to write forms or kata for martial arts training