I think that training ought to be focussed and goal oriented. The goal in any fencing context is to strike without being struck, so any problem can be thought of as “I’m getting hit” or “I’m not hitting”. Drills are the means by which we fix either of these core problems.

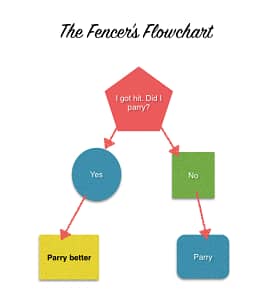

Let’s start with the “I got hit” problem. Here is a snazzy little flowchart:

Yup, it boils down to this: the only reason you ever get hit is because you failed to parry. The hit is never wrong. This is really important. When we are past the point of teaching beginners the absolute basics, we don’t solve the problem of being hit by changing the attack. The attack is supposed to hit.

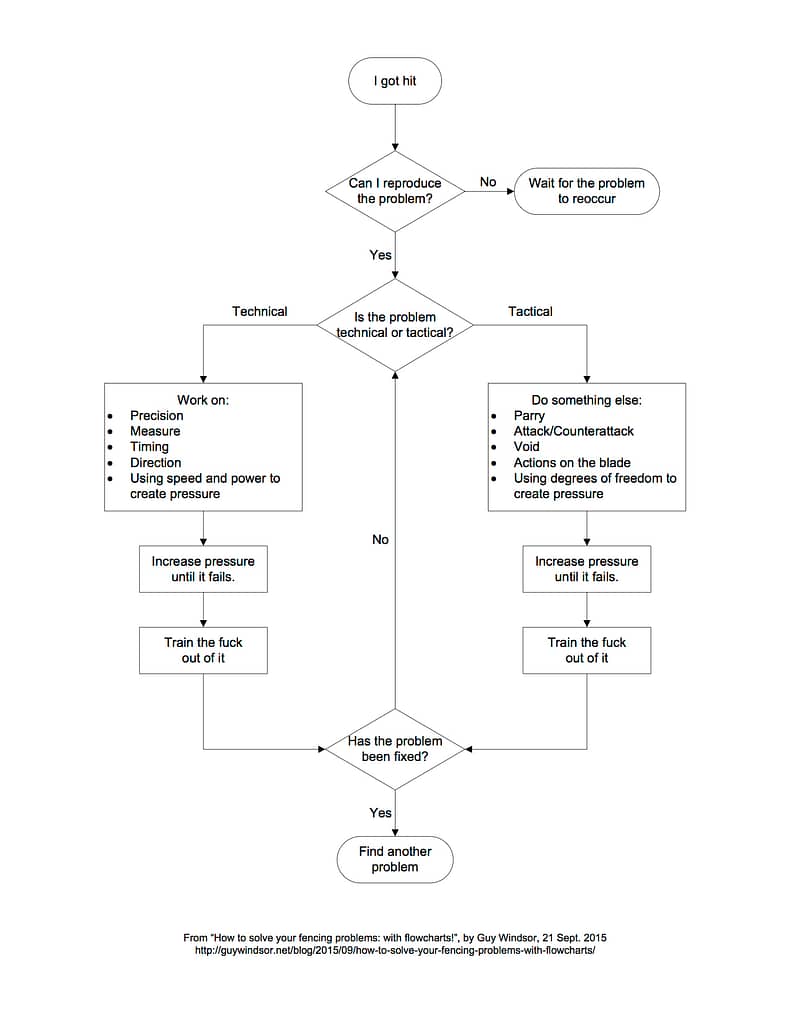

So whatever your current fencing problem is, here are the steps to fix it:

1) Reproduce the problem. If you can’t reproduce it, it was either a fluke, and so not something that can be trained against, or you didn’t understand what happened. You can’t fix training problems you don’t understand, so if that happens, find somebody to explain what happened to you. Your opponent might do that, or your teacher.

2) Analyse why you are getting hit. You are either doing the right thing, but not well enough, or you are doing the wrong thing. So the problem is either technical, or tactical. These have quite different solutions.

Technical problems are solved by training the technique in increasingly challenging contexts. In short, slow down until it works, then ramp up the speed and power gradually until you can do it at the necessary level. I think of this as solving problems of incompetence.

Tactical problems are solved by choosing a better solution at the critical moment, which you learn to do by using drills with ever increasing degrees of freedom. I think of this as solving problems of ignorance.

So whatever drill you are doing should be solving a specific problem of either ignorance or incompetence making you wiser and better.

(The specific details of how to use pressure and degrees of freedom are in Preparing for Freeplay. They are also described in The Medieval Longsword.)

I have put all this together in another nifty flowchart. The original was done by me in Scapple, which is a great app for thinking with, but doesn't do pretty charts. Several kind and lovely readers have sent me much prettier versions, of which this, by Andrew R. Mizener, is the clearest.

Thanks Andrew! (I absolutely love it when my readers step up and help. Really, it's the best feeling.)

If you’d like specific examples of drills that solve technical or tactical problems, let me know in the comments.