In “Following my own advice” I described how I try to get something important done every day before checking emails. In that post I rather blithely referred to concentrating on ‘creating assets’, and loosely defined assets as “anything that adds value to your life. Value in this case is usually either money, or reputation, or both.”

I’ve had a lot of interesting feedback on the post, mostly through my mailing list (feel free to join below), and one point that came up more than once is that I didn't define ‘assets’ clearly enough, so I thought I’d go through in detail what I think I should be spending my time on.

You spotted how I carefully did not say “you should be spending your time on”, right? As ever, take my advice with a sceptical mind, and discard anything that doesn’t work for you. One big caveat: being self-employed means I have a dick of a boss who never gives me time off or a raise, but I can choose literally anything to work on. That's both a blessing and a curse.

Here is the Master Asset List, my top three assets, in order of priority.

1) Mental Health

Every experience you will ever have is mediated and experienced by your consciousness. There is no experience so blissful that you can’t be miserable during it, and no experience so awful that bliss is impossible. Perhaps the best single resource on this is Sam Harris’ book Waking Up, closely followed by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s book Flow. The key elements to my mental health are:

1. My relationships (primarily wife and children, other family and close friends, everyone else).

2. Meaningful work. Like writing this blog post. Or the next book. What makes it meaningful for me is its ability to transform other people’s lives for the better.

3. Meditation. I meditate every day, and have been doing so (with more or less regularity) for many years. The last year or so has been especially difficult (see here for an idea why), and one of my coping strategies has been to get a lot stricter about doing my meditation every day. It helps. I’ve written a short guide to getting started if you want to try it out.

4. Fun. Much underrated, but it is critically important to kick back and have fun often. Never underestimate the power of silly.

All the rest of these assets listed below are only relevant or useful because they affect my state of mind. It’s easier to be mentally healthy when you’re physically healthy and not worried about money.

2. Physical Health

“If you haven’t got your health, you haven’t got anything.” Count Rugen was a villain, but he spoke truth here. Physical health rests on two foundations: what you eat and how you move.

Diet: I’ve written up my approach to diet in lots of places, including here, here, and here; and it can be summed up as:

- learn to cook

- avoid sugar

- eat lots of vegetables

- pay attention to high quality fats, and

- fast every now and then.

That's a very big topic dismissed in a few lines, so do check out those links if you're interested.

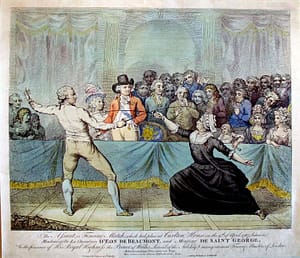

Exercise: How you move… hmmm, I wonder what kind of exercise a professional swordsman would recommend… ok, start with looking after your joints (here’s a free course on knee maintenance), and carry on by finding any physical activity that you enjoy, and do it regularly. That could be walking the dog, ballet, rock-climbing, trapeze, anything. Some activities are better adapted for long-term health than others, but if health is your priority you can probably avoid most of the damage that might be done during the less conservative activities. I’m a big fan of breathing exercises, as you probably know; they are the foundation of my movement practice, and they are specifically designed and intended for promoting health.

An imperfect plan that you actually follow is way better than a perfect plan that you abandon, so it’s much more important to find something fun that keeps you moving, than it is to find the ‘perfect’ health-giving exercise. Moving your body should not be a chore.

Sleep: The best single source on sleep matters (and sleep does matter!) is Matthew Walker’s Why We Sleep. In short, the more and better you sleep, the longer you live. Good sleep is really the ultimate time management strategy because it a) buys you more time because you live longer and b) makes your waking hours vastly more productive. There are so many factors affecting sleep that it would take a whole book to go into them (like Dr. Walker’s!), but I’ll summarise the main things that have helped me:

- Avoid caffeine for at least 12 hours before bedtime. Yes, 12 hours. I only drink coffee at breakfast. Caffeine kills deep sleep.

- Avoid alcohol, or at least get it all out of your system before bed. Alcohol kills REM sleep.

- Keep the bedroom dark, cool, and quiet.

- Stop eating at least 3 hours before bed. A full stomach affects sleep quality.

- Nap, but not too long or too late. eg 30-60 minutes at 2pm.

- All screens off at least an hour before bed, and screens after 8pm are set to ‘Night Mode’, cutting down on blue light.

I could go on, but you get the picture. As with everything, experiment to see what works for you. I track sleep with the OURA ring, but you can use other tools, or just notice how you feel in the morning. Top tip: if you need an alarm to wake up, you haven’t slept enough.

3. Money

Once your mental and physical health are being attended to, then the next big thing is money. Money worries are truly toxic to your mental health, and can poison every aspect of your life. Think of those bankers jumping out of windows during the Great Depression, all because some numbers on a bit of paper were not the way they wanted them. Weird, huh? But real. Just choosing not to worry is an option, of course, but it's much easier for most people to actually do something to reduce expenditure and increase income. Incidentally, my favourite money blog is Mr Money Moustache. He's refreshingly unapologetic.

I should point out that I am by no means rich- I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of months since I became an adult in which I had enough cash in the bank to cover the next month’s bills in advance. This is because I have always, always, put time-rich ahead of money-rich, on the grounds that you can always make more money but when time is spent, it’s gone for good. My first salary as a cabinet maker was £6000 per year. I learned fast enough to double that in two years. Woohoo! And swordsmen these days don’t make much cash either.

In Finland, people’s tax returns are actually in the public domain- you can literally walk into the tax office and for a small fee get a copy of anybody’s. Let me save you the bother: here’s mine from last year in case you’re interested.

But, and here’s the big BUT. Since the beginning of 2015, I’ve been effectively living off passive income. My books and other assets generate about enough money to live on, month by month. People buy my books and courses while I’m asleep. And, given that I’ve never made a lot of money, I’ve never become addicted to a large and regular income, so it took relatively little time or effort to get to the point where my assets were generating enough income to cover all normal expenses. This means that I am now much freer to choose the things I spend my time on. Like taking all day Wednesday off this week because it's my daughter's birthday and she has stuff planned from dawn 'till dusk.

In short, my work priorities are:

- do I think it's important, in terms of serving the art?

- will it be good for my reputation?

- will it force me to acquire new skills?

- will it produce passive income?

- is it scalable?

Let's take those one at a time:

1. Serving the art: In my experience, every single time I've tried to be ‘businesslike' and put what should be a sensible business move in place it's gone horribly wrong. But when contemplating a course of action if I can look into my heart and say ‘yes, this will serve the art', then it's always turned out ok (even if it hasn't made any money).

2. Reputation: Not every asset generates income: some generate opportunity. When The Swordsman's Companion was published in 2004, it made me no money at all (there’s a story there, but after suing the publisher, part of the settlement included a mutual non-defamation agreement. Make of that what you will). But that book put me on the map as an instructor. I suddenly started getting invited to events to teach, which massively broadened my horizons. Students from all over the world started to get in touch, having heard of me because they found my book in a bookshop somewhere. My Singapore branch came into being because Chris Blakey and Greg Galistan stumbled upon my book in the Borders Bookshop there. And when the rights reverted to me in 2012, I self-published it, and now it pays the mortgage.

3. Acquire skills: Time spent working on skills is never wasted, especially skills that you learn for their own sake rather than for a specific objective. Because whatever skill you are learning, you are simultaneously learning how to learn, and, more importantly, if you’re learning for its own sake you are putting process over outcome. Let’s say I learned to speak German because I wanted a job in Germany. If I learned German but didn’t get the job, the time would have been wasted, and I wouldn’t take full advantage of being able to talk to Germans in their own language, to read German books and watch German films. But if I learned German for its own sake, and it happened to lead to a job, well that’s a bonus.

A skill become an asset when they add value to your life. I really cannot think of a single skill I’ve ever regretted learning. And I can think of several that I learned ‘just because’, that then turned out to be professionally useful. Martial arts being the obvious example- I didn’t even think of turning professional until 2000, and I had about 15 years of training under my belt by then!

4. Passive income: There is nothing wrong with being paid for your time. And nothing wrong with being productive. But even in the classic model of employment, you’re supposed to retire at some point and live off your pension. Your pension is created by investments that pay you a passive income. This is how people in professions like dentistry can end up retiring in comfort- they make a good income per hour, being paid by the hour, but use a big chunk of that active income to buy assets (such as stocks and funds) that produce a passive income.

A passive income is defined as income that requires no work on your part whatsoever. If you are packing and shipping your own books, that’s not passive income. If you have to be in a specific place, or awake at a specific time to get paid, that’s not passive income. When I am faced with a choice between producing something I can get paid once for (a woodworking commission, a writing commission, private lessons, seminars etc), or producing something that will generate a passive income stream, even a small one, then I will tend to choose the latter.

Perhaps the most outrageous examples of this choice comes from the original Star Wars movie. Carrie Fisher sold her image rights outright for a sizeable chunk of money. Over a thousand dollars, I think, way back in the 70s when that was worth something. Alec Guinness got paid royalties. Guess which one did better? There was a lot of luck involved, but if you don’t have passive-income producing assets that might go all Harry Potter on you, then it cannot ever happen.

Let’s put some numbers on this. The Swordsman's Companion makes about 10,000 dollars a year in income for me (it’s my best-selling book by a margin!). To generate similar returns, I would need at least 200k in traditional assets. Here’s an article on how that would work. If anyone wanted to buy that book off me outright, I’d therefore ask for at least 200k. Nobody in their right mind would offer me that much, so the book stays with me. Folk might stop buying it tomorrow. But folk might still be buying it in 50 years time. There is no way to know, and that is true of any asset. Stock markets crash like Italian drivers. There is no such thing as a perfectly safe investment- even cash loses value over time. My mother in law saved for a pension for 30 years- and just before she was due to retire, the fund (Eagle Star) crashed and she lost the lot. Nothing is safe, so the only sane course is diversification, which is why you can buy my books on any platform, in any format- so long as people still want to read about how to train with swords, they will be able to buy my books on the subject.

5. Scalable: A scalable asset is one which you create once, and can sell an infinite number of times. I have spent most of my working life producing non-scalable assets. Back when I was a cabinet maker, I would work for hours and hours on a piece of furniture, which was then sold. As a martial arts teacher, I would teach a class, which existed only in that moment. I got paid for that moment, but that was it. There is nothing wrong with this model if you have the energy to work full time forever, and never get sick. A non-scalable asset might produce passive income, but you can still only sell it once. A house that you rent out is a good example. It can be an excellent passive income stream, but you can only rent the house out to one tenant or group of tenants at a time.

A book is scalable- you write it once, and when it’s published people can buy as many copies of it as they want. You don’t have to write each reader a new book. An online course is scalable too; create it once, sell it as many times as you like.

Ideally, my most productive time is spent serving the art, building my reputation, learning skills, and producing scalable assets that produce passive income.

So, that's how prioritise my time; how do you prioritise yours?

This will be my last post this year, so let me close by wishing you a Merry Christmas, and a happy, mentally, physically and financially healthy New Year!