For an academic, it is the best feeling in the world when the ground you have built a mansion on starts to tremble. (Less so for an architect, I’d imagine.) I had that experience on my recent trip to the Panoplia Iberica where I finally met Dario Magnani in person. He runs the THOKK gloves enterprise, and is a keen Fiore scholar. We talked for literally hours about the most minute details of our interpretations, starting with his take on the famous “three turns of the sword”. It was so much fun I got him onto my podcast to revisit the topic, which you can hear here:

What is a volta? A very detailed examination of Fiore, with Dario Magnani

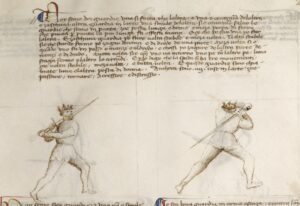

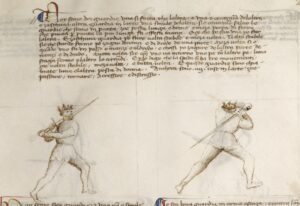

I’ll go through the passage first, then describe my current interpretation of it, then his take on the same text, and then sum up. We’re talking about folio 22 recto from the Getty manuscript. I’ll quote the transcription, translation, and interpretation from pages 116-117 of From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice: The Longsword Techniques of Fiore dei Liberi.

What does Fiore dei Liberi say?

The text reads:

Noy semo doi guardie, una si fatta che l’altra, e una e contraria de l’altra. E zaschuna altra guardia in l’arte una simile de l’altra sie contrario, salvo le guardie che stano in punta, zoe, posta lunga e breve e meza porta di ferro che punta per punta la piu lunga fa offesa inanci. E zoe che po far una po far l’altra. E zaschuna guardia po fare volta stabile e meza volta. Volta stabile sie che stando fermo po zugar denanci e di dredo de una parte. Meza volta si e quando uno fa un passo o inanzi o indredo, e chossi po zugare de l’altra parte de inanzi e di dredo. Tutta volta sie quando uno va intorno uno pe cum l’altro pe, l’uno staga fermo e l’altro lo circundi. E perzo digo che la spada si ha tre movimenti, zoe volta stabile, meza volta, e tutta volta. E queste guardie sono chiamate l’una e l’altra posta di donna. Anchora sono iv cose in l’arte, zoe passare, tornare, acressere, e discressere.

We are two guards, one made like the other, and one is counter to the other. And [with] every other guard in the art one like the other is the counter, except for the guards that stand with the point [in the centre], thus, long guard and short, and middle iron door, that thrust against thrust the longer will strike first. And thus what one can do the other can do. And every guard can do the stable turn and the half turn. The stable turn is when, standing still, you can play in front and behind on one side. The half turn is when one makes a pass forwards or backwards, and thus can play on the other side, in front and behind. The whole turn is when one goes around one foot with the other foot, the one staying still and the other going around. And so I say that the sword has three movements, thus stable turn, half turn, and full turn. And these guards are called, one and the other, the woman’s guard. Also there are four things in the art, thus: pass, return, advance, and retreat.

What do Fiore's words mean?

Let me unpack this:

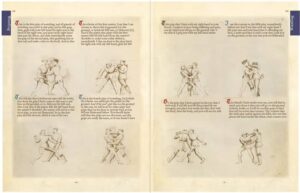

1. The two guards shown are both posta di donna. One is shown forward weighted, the other back weighted. I interpret the difference between them to be a volta stabile (more on that later).

2. Any two guards that are alike can counter each other.

3. Except for guards that have the point in the centre line (longa, breve, and mezana porta di ferro; more on those in the next section). This is because the longer sword will strike first. Here I’m translating punta as point (stano in punta, stand with the point), and thrust (punta per punta, thrust against thrust). The meaning is obvious whichever way you translate it though: don’t stand with your point in line against someone else who has their point in line unless you have the longer sword.

4. Any similar guards can do what the guards they are like can do.

5. Every guard can do the volta stabile and the meza volta. (I use the Italian terms for technical actions, guards, etc. where possible. Refer to the glossary [link] if you need it.)

6. The volta stabile: I interpret stando fermo, standing still, to mean without stepping, or moving a foot. As I do the volta stabile, the balls of my feet stay on the same spot on the ground. It makes no sense for a turning action to involve no movement at all, so standing still cannot mean literally ‘not moving’.

7. The meza volta: this is a passing action, forwards or backwards. I interpret that to include a turn of the hips and body, so you go from one side to the other.

8. The tutta volta: here again we have a ‘fixed’ foot, that, unless your legs are made of swivel-joints (top tip: they’re not), must at least turn around itself for the action to occur. This supports my reading of stando fermo above. Simply, this is whenever you pivot on one foot by turning the other one around it. There is a video of me doing these three movements linked to further on in this chapter.

9. The sword also has three movements: stable turn, half turn, and full turn. Unfortunately there is no further discussion of this, and these terms simply aren’t used in the rest of the book. Fiore will tell us to ‘turn the sword’, for instance in the play of the punta falsa, on f27v, but never with the qualifiers stable half or full. So I simply do not use these terms to apply to sword actions. Other instructors and interpreters do, but you should be aware that there is no evidence supporting any one interpretation of these turns over another.

10. In case you missed it the first time: both these guards are posta di donna. Both of them. Got that?

11. There are four things in the art: pass, return, advance and retreat. See the video: three turns, four steps: https://guywindsor.net/lgg01

Okay, so that’s the current state of affairs, and it accords with what most Fiore scholars I know think of the three turns.

Dario’s reading is different though. In essence, he thinks that the volte Fiore is describing here are specifically the turns of the sword. Or better, the movements of the sword.

In other words: a volta stabile is what you can do moving the sword forwards and backwards while standing still. For example, thrust from breve to longa without stepping at all.

A meza volta is what you do with the sword when passing forwards or backwards, and the sword goes from one side of the body to the other. This could be a blow, or just changing guard.

A tuta volta is what you do with the sword while turning one foot around the other.

This makes sense for the following reasons:

1. Why would footwork come between the sword in one hand and the sword in two hands? Surely if this was meant to be a purely footwork description, it would be earlier in the manuscript.

2. The volta stabile as we do it as a footwork action cannot reasonably be described as ‘standing still’. It took some wrangling to get it to apparently mean that (as you can see in points 6 and 8 above).

3. The line “And so I say that the sword also has three movements, thus stable turn, half turn, and full turn” can be read as a summary of the preceding sentences, not an application of footwork actions to the sword. The “also” there doesn’t come from “anchora”, it’s more pleonastic: it comes from E perzo digo che la spada si ha tre movimenti, zoe volta stabile, meza volta, e tutta volta. That bit “la spada si ha” literally means “the sword it has”. There’s really no “also” in that sentence, thought I’m not alone in inserting one: Leoni translates it as “the sword also has” (Leoni and Mele, Flowers of Battle vol. 1 page 252). Drop the questionable “also”, and the sentence reads as a summarising of the preceding three turns as turns of the sword.

4. Volta has many meanings and shades of meaning. You can find literally dozens of meanings for it on pages 1000-1002 of Battaglia’s dictionary, online here: https://www.gdli.it/sala-lettura/vol-xxi/21 Dario’s contention is that these actions don’t have to be read as specifically turning actions (which allows for a simple thrust from breve to longa to be a ‘volta’). To be honest, that’s the hardest part of this for me- I haven’t found a solid linguistic reference to justify a non-circular interpretation of the word, though the expression “dai volta”, lit. ‘give turn’, means “get a move on”.

It is very convenient to translate words that may have many meanings into simple, specific, and concrete technical actions. The volta stabile then gets to be one simple thing, easy to explain and teach, rather than a class of things (what you do with the sword while standing still). But this can be a false sanctuary. Likewise with the final sentence of this troublesome passage: “Anchora sono iv cose in l’arte, zoe passare, tornare, acressere, e discressere. Also there are four things in the art, thus: pass, return, advance, and retreat.”

These have long been interpreted by me and just about everyone else as passing forwards, passing backwards, stepping forwards, stepping backwards.

We know from the definition of the meza volta that ‘passare’ means to pass forwards or backwards. What is ‘tornare’ then? It means return, and when we see it in action, such as in the defence of the dagger against the sword thrust on f19r, “Lo pe dritto cum rebatter in dredo lu faro tornare”, it isn’t a pass at all: it’s the withdrawal of the front foot (see From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice pages 44-47 for the transcription, translation, and video).

Likewise the discrescere that we find on f26r when we slip the leg against a sword cut; it’s not a step backwards; your back foot doesn’t move.

So our neat classification of footwork actions starts to fail.

So is this passage, the beginning of the sword in two hands section, all about how the sword moves? That would not be a stretch. And for sure the volta stabile is not a great big movement of the body. I’ve started calling that movement (which is still a fundamental part of the art) a “volta stabile of the body”.

I’m not sure where I stand on all this yet. I’m convinced of one thing though: it’s past time to return to the assumptions that I have based my interpretations on and work through them with ever-closer attention to the text.

And if you listen to the podcast episode, you'll hear the moment when I'm convinced that the “also” has to go!