My friend and colleague Malcolm Fare, proprietor of the National Fencing Museum, would like to know if anyone reading this is familiar with the Grand Salute, as formalised by the Académie d'Armes de Paris in 1888.

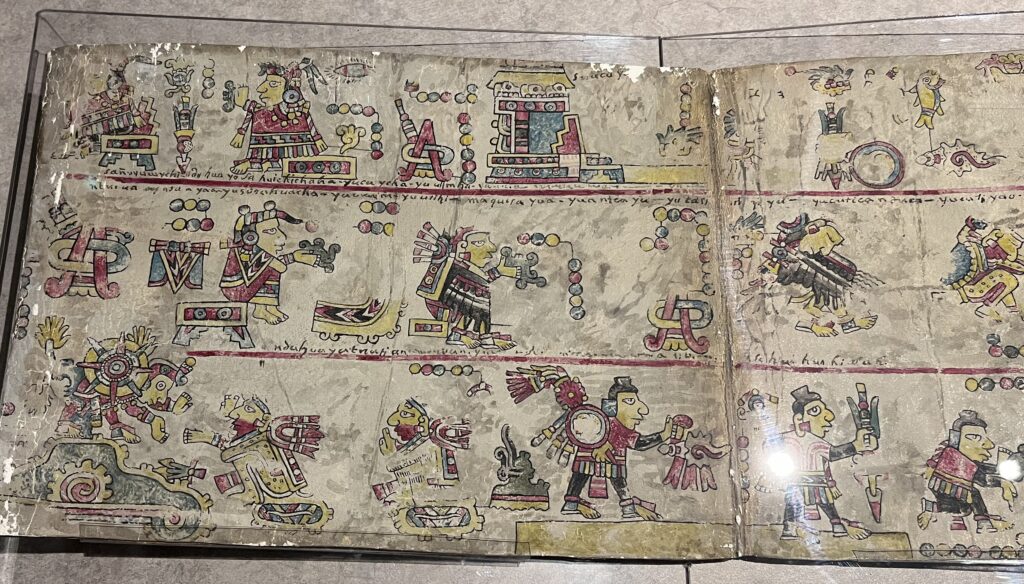

As the editor of The Sword magazine, he published an account of the Grand Salute in 1995. You can see the article here:

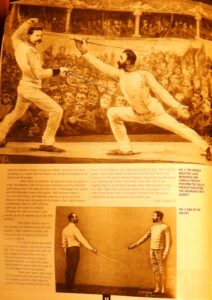

The article was prepared by the fencing coach Eric Howlett (1921-2015), who translated the text from L'Escrime et le Duel by Previost & Jolivet, 1891, with captioned photos by Nadar of the various moves.

Here's the text in a more accessible format (this may not be a perfect transcription):

The Grand Salute

Before the days of competition, when important displays of fencing were watched by thousands of spectators, an essential prelude to the assault was the salute. Its purpose was to give both fencers an opportunity of showing courtesy to each other and to the spectators, and of exhibiting their own proficiency in correctness and elegance. Practised in various forms by different schools, the grand salute was formalised by the Académie d’Armes of Paris in 1888. It consisted of 66 movements as follows:

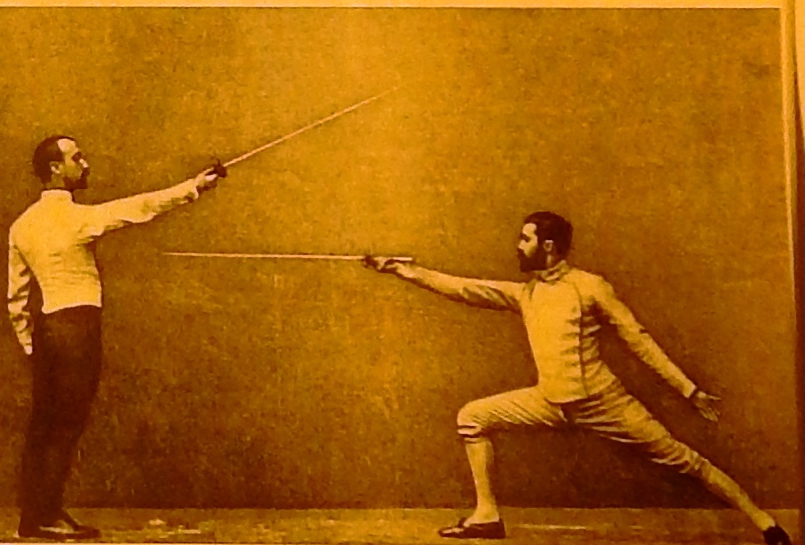

Fencers take up position (fig. 1) just out of distance, masks and gloves laid down to the left of their left feet. Each salutes to the left and right, coming on guard in sixte and then momentarily in tierce; immediately the blades have met, the hands turn to resume the guard of sixte.

One of the fencers, usually the elder, invites the other with the words “You have the honour”; the junior replies “Yours to command” and the senior says “Begin”. The junior fencer then executes a flourish to bring the sword arm in line horizontally and lunges, the point falling short of the target by an inch (fig. 2). He then resumes his standing position with arm and blade at 45 degrees in one movement.

Both fencers, acting together, salute in quarte, then in tierce, resume the first position for an instant, then sweep the foils down and back, pausing with the left hand (knuckles down) on the blade and both arms extended downwards (the blade being horizontal and the point to the rear). From this position the foils rise horizontally (points to the rear) till the hands are as high as possible. The fencers then fall on guard in sixte, the right and left hand separating gracefully; the senior fencer then closes the line of sixte, the junior disengages with full extension, and the senior executes a smart beat in quarte. As the parry is made, the attacker throws his point upwards and backwards past his own right ear with a quick movement of thumb and forefinger (fig. 3). While this swing is taking place, he lunges, and as he does so the defender’s foil passes to septime as if threatening a riposte in the low line. The attacker then resumes the on guard position, bringing his foil in line in the horizontal plane to meet the defender’s foil coming up into a bind of quarte.

The attacker then disengages as before, but in sixte, and the defender beats in tierce, lowering to seconde. On the beat the attacker relaxes his grip as before, but turns his hand on doing so in order that the blade may swing horizontally to his left ear as he lunges.

After these movements, the fencers come on guard in sixte, the attacker with foil and arm extended and the defender with elbow bent. The attacker then does a disengage into quarte and the defender covers into quarte. Both fencers make a cut-over into tierce, the defender staying on guard and the attacker falling back on guard as the blades click. Both fencers immediately beat or call with the right foot and come to a stand (bringing the right foot back) with points up at 45 degrees as in the first position.

The senior fencer now in turn proves his distance and recovers position. Both salute in quarte and tierce and fall on guard, circling the blades as before.

The senior fencer proceeds to make his attacks, just as the junior did. It is a point of style that each of the lunges be faster than the last. The cut-over one-two to a stance forward and the cut-over into tierce, falling back on guard with the beat of the feet, again follow the attacks.

Next each fencer falls back to the stance with arm and foil up at 45 degrees and then falls back on guard, making a wide cut-over into tierce out of distance; they beat twice with the feet. Then, still on guard, they make sweeping salutes to quarte and tierce and come up to the stance forwards, blades vertical and guards to the lips, saluting each other. Next they lower their foils to 45 degrees (fig. 4), or cut them sharply away with a swish to the low right. Apart from while the words are exchanged, one or both of the fencers are in movement all the time, the whole ceremonial being consecutive and continuous.

Call for videos!

I'm aware of this apparently authentic but incomplete version of the salute here:

Does anyone here practice the Grand Salute, and if so, could you video it for Malcolm? If you do, let me know either in the comments here, or by email through my contacts page above.