Academic research is the foundation of Historical Martial Arts. When you try to recreate an action described in a book, that’s academic research. When you try to figure out what a particular phrase in a source means, that’s academic research.

Most mainstream academic research is presented in a way that is deliberately hard to get access to, and often deliberately hard to read. The only reason to publish that way is to get jobs at universities.

Historical martial arts books are usually written for practitioners. All of mine are, so I need my research to be perfectly clear and easy to distribute among the active historical martial arts community. I want my work to be accessible to beginners, experienced fencers, and my fellow instructors.

If you want your academic work to appear in academic journals, you need to find out what that journal wants, and present your work the way they ask. But if you want it to be of maximum use to the HMA world, this post will show you how I think you should go about it.

This is a big post, and not all of it will be relevant to your needs, so here's a table of contents to guide you through it. I've written each section to be reasonably independent, so cherry-pick what you need:

Introduction

Many historical martial artists generously share their interpretations, but do so in a way that makes it impossible to check their work. Simply doing the action in a video and posting it online is helpful to people who want to know how you do it, but useless for establishing whether it’s an accurate interpretation of the source. For that you need at the very least to quote the source, and explain any interpretive decisions you made. Video is not a good medium for that; it’s far too slow, and far too difficult to check the text. Books are better, but suffer from other limitations, such as being unable to show movement. The ideal way to show your work is to combine books and video. This post will show you how I do that.

It’s important to note that academic work is the foundation of our knowledge of Historical Martial Arts. But it has no necessary connection to our martial skill. You can be highly skilled in an interpretation and be able to teach it, fence with it, and apply it in all sorts of situations, without even knowing the name of the source it is originally based on. Likewise, you can be incredibly knowledgeable about a given source and be able to perfectly recreate the choreography of every action, without having any fencing skill at all. Most historical martial artists are somewhere in between.

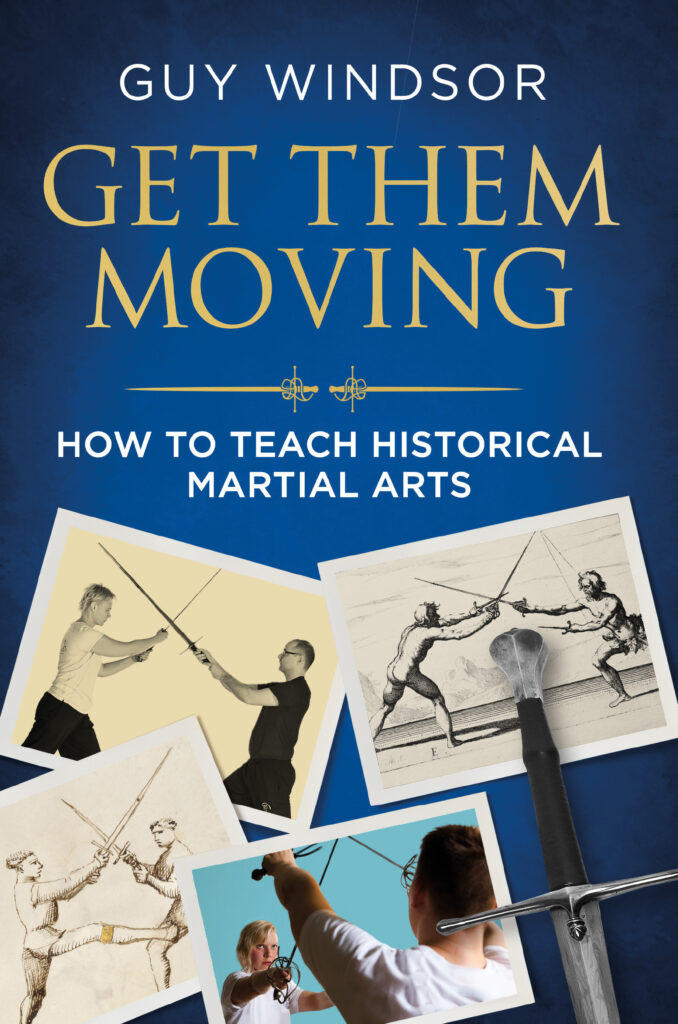

In this guide I am only dealing with the academic side of things. I have a whole other book on creating training manuals for developing skill. You can find it at here.

What kind of work are you doing?

Before you present your work to the world, you need to know what kind of book it is. There are at least five different kinds of modern HMA publication.

- Facsimile. This is a printed copy of scans of the source. The ideal is to make it as close as possible to owning an original copy of the source. This is not an academic work, usually. It’s much more of an art project.

- Transcription. You take the trouble to type out the entire source (or part of it). This makes it much easier for people to use the source, because the electronic version of the transcription is now searchable.

- Translation. You translate the source from one language to another. Personally, I much prefer a translation to include at least a transcription, or a full facsimile, so I can check the translation against the source. This should also include copies of the images in the source if there are any.

- Interpretation. You demonstrate how you think the actions in the source should be done in practice. This can be through text and images, or through video.

- Training manual or workbook. You teach the student how to execute your interpretation as a living martial art. This can also be done through online courses.

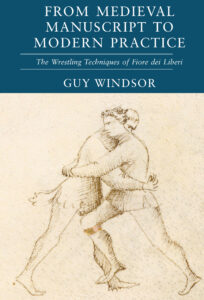

It is generally not practical to create a book that is all five of these things in one volume. It would simply take up too much paper. It is much easier to demonstrate movement on video, but video is hopeless for sharing a transcription or translation. And a facsimile is by definition in the same general format as the source, which is some kind of book. But these five categories can overlap considerably. My From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice includes transcription, translation, and interpretation. But it’s not a facsimile, and it’s not a training manual.

I have produced all of these types of publication, in one form or another. Such as:

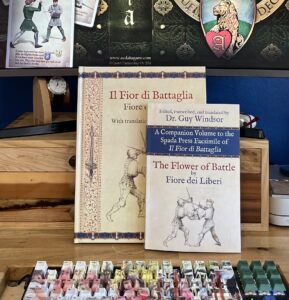

Facsimiles: I have published facsimiles of Fiore dei Liberi’s Il Fior di Battaglia (Getty Museum MS Ludwig XV 13), and Philippo Vadi’s De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi, (Biblioteca Nazionale di Roma MS Vitt.Em 1324). These are both affordable un-fiddled-with reproductions of the manuscripts, with a single-page description of what they are and where they come from at the back. It’s as close as you can get to owning the manuscripts themselves for under $50.

Michael Chidester at HEMA Bookshelf does much fancier facsimiles, in gorgeous leather bindings, and much higher production values, which is as close as you can get to owning the manuscripts, for under $500.

Transcriptions: I include transcription in my From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice series, and also produced a transcription of Vadi which I released free online. There are many other researchers who do the community a huge service by producing and releasing transcriptions of all sorts of other works. These are usually available online somewhere.

It’s actually quite unusual to find a pure transcription (with no facsimile or translation) published as a commercially available printed book.

Translations: my first properly published translation is in The Art of Sword Fighting in Earnest. This is my translation and commentary on Vadi. I licensed the translation under a Creative Commons Attribution licence, which means it is free to use and share in any way, you just have to give credit. Perhaps the gold standard in translations are Jeffrey Forgeng’s translations of the Royal Armouries MS I.33, published as The Medieval Art of Swordsmanship and of Joachim Meyer’s treatise published as The Art of Combat.

Interpretations: they say there is no translation without interpretation, and that’s largely true. How you understand the text will influence how you translate it. I include interpretation in most of my works, including From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice, and The Duellist’s Companion. There are many, many, published interpretations out there.

Training manuals: a training manual teaches you how to train in a particular interpretation. It does not usually include much about why you think the source means what you think it means. It must by default include your interpretation, but it does not usually show your working. The three books in my Mastering the Art of Arms series, The Medieval Dagger, The Medieval Longsword, and Advanced Longsword, are all training manuals.

Workbooks: a workbook is a training manual that is formatted for the student to make notes in. The difference is primarily in the format, though a workbook will usually have even less academic content than a training manual. I have a series of four workbooks for the rapier, combined into The Complete Rapier Workbook, and the first in what will probably be a series for Fiore’s Art of Arms, The Armizare Workbook, part one: Beginners.

As you can see, I’ve produced works of all five kinds (not to mention a book of mnemonic verses: The Armizare Vade Mecum).

Now that we have defined some terms, let’s go through the list and have a look at how to present your transcription, translation, and interpretation. Facsimiles are a separate category, and so are training manuals. I’ve written a whole other book (From Your Head to Their Hands: how to write, publish, and market training manuals for historical martial artists [link]) on, you guessed it from the title, how to write training manuals, because it’s the one kind of book that you actually write from scratch. Each kind of book will need a somewhat different introduction, so I’ll include specific instructions for the introductions too.

Transcription

Transcription introduction

Your introduction should answer the following questions:

- What book or other source are you transcribing?

- What versions of the source exist, and why have you chosen this one?

- Where can that source be found?

- Who wrote it?

- What do we know about the author?

- What images do we have, and are you reproducing them?

- What kind of transcription are you trying to produce? Where on the “diplomatic” scale do you fall?

- What conventions will you be following regarding contractions, suspensions, brevigraphs etc.?

- Who are you and why should the reader trust you?

You can find a very useful guide to transcription conventions, published by the University of Hull, here: guywindsor.net/transcriptionconventions (that's a redirectable link in case the article gets moved).

Transcription layout

You need to make a decision about whether to include scans of the original sources in your work. In general, if you can (due to copyright restrictions etc.), do. It’s much better to present the reader with the chance to check your work. This is especially true if you are transcribing a manuscript. If you are making a machine-readable copy of a perfectly clear-to-read source, then you don’t need to include the original.

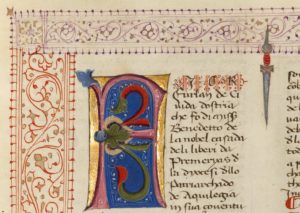

If you are going to include scans of the original source, then layout becomes an issue. For instance, the first page of Fiore’s introduction is laid out in two columns, with a fancy capital. The text also continues onto the next page mid-sentence.

You basically have two options. You can reproduce your transcription and keep all of the layout decisions, so arrange your transcription on the page the same way Fiore does. Or you can arrange it separately. My preference would be to reproduce the whole source intact, and then present the transcription separately but with the same basic layout. That makes it much easier for readers to find the original source for any give bit of transcription.

If you are quoting from a part of the transcription that includes a page break, note the point of the break by putting the page reference in square brackets, such as:

… l'o mostrada sempre oculta mente si che non gle sta presente alchuno [page break: F1r to F1v] a la mostra se non lu Scolaro,…

Or more simply:

…l’o mostrada sempre oculta mente si che non gle sta presente alchuno [F1v] a la mostra se non lu Scolaro,…

Translation

Translation introduction

Your introduction should answer the following questions:

- What book or other source are you translating?

- What versions of the source exist, and why have you chosen this one?

- Where can that source be found?

- Who wrote it?

- What do we know about the author?

- What images do we have, and are you reproducing them?

- What kind of translation are you trying to produce? Where on the “literal” to “analogous” scale do you fall?

- Who are you and why should the reader trust you?

Translation choices

Because of the interplay between translation and interpretation, we should discuss what kind of translation you doing. However you choose to do your translation, you need to make your approach clear in your introduction, so readers know what to expect.

A strictly literal translation translates each word in the source in turn, without reference to the meaning of the phrase, sentence, paragraph, or rest of the book. This is also called a direct translation, a word-by-word translation, or a metaphrase. Generally speaking, this is not a useful approach. How would you translate the word “match” in this sentence: “I met my match while striking a match at a football match”?

Beginners are often surprised or even upset to find that the same word is apparently translated differently in different places; this is only because they don’t understand that the context the word appears in is different. Languages are not ciphers of each other- you can’t simply convert each word and expect to find the meaning.

An analogous translation translates the meaning of the source into the target language. This is also called a paraphrase. This would allow you to translate “match” in three different ways based on those three meanings, as made clear from the context. Taken to extremes though, this can lead to translation decisions that fail to properly convey what the original author said.

All translations exist on a spectrum from 100% metaphrase to 100% paraphrase. You have to decide where on that spectrum you want to work, and what point is most useful to your target readers.

To my mind, it’s more useful to translate a bit too literally than a bit too freely. A lot of the readers of these translations are using them to teach themselves to work with the original sources. Over-interpretation makes that much harder.

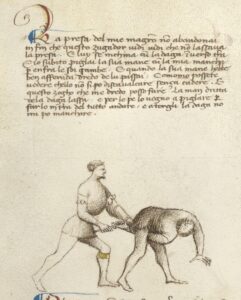

Let’s take this phrase from Fiore, for example. It is part of the text regarding the punta falsa play, on f27v.

…Io mostro d’venire cum granda forza per ferir lo zugadore cum colpo mezano in la testa. E subito ch’ello fa la coverta, io fiero la sua spada lizeramente. E subito volto la spada mia de l’altra parte piglando la mia spada cum la mane mia mancha quasi al mezo. E la punta gli metto subita in la gola o in lo petto…

My translation in From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice:

I show that I am coming with great force to strike the player with a middle blow in the head. And immediately that he makes the cover I strike his sword lightly. And immediately turn my sword to the other side, grabbing my sword with my left hand at about the middle. And I place the thrust immediately in the throat or in the chest.

Tom Leoni’s, in The Flower of Battle, vol. 1, page 275

… I feint a strong mezzano to the opponent’s head. As he forms his parry, I lightly strike his blade, then immediately turn my sword to the other side, grasping it almost at mid-blade with my left hand. I can then place a quick thrust to his throat or chest…

I have a huge regard for Tom’s translation work, but every now and then he strays a bit too far in the analogous direction. Fiore’s description “I show that I am coming with great force to strike the player” becomes “I feint”. He also uses “forms the parry” for “makes the cover”, “opponent” for “player”, and I’d have to say that “mid-blade” is clearly not in the text (it’s just “at the middle”).

I should note that The Flower of Battle quoted here is an absolute gem of a book, and a must-read for any Fiore scholar. And I agree very much with most of the translation.

If you are faced with a phrase that has no meaning in the target language, then I would still translate it as written but add its equivalent phrase in a footnote. For instance, when Vadi wrote Et romperoti il brazo al diri dunave (on f20r), it means ‘And I will break your arm while saying a Hail Mary’. So that’s how I translated it. But I included a footnote which reads:

Though the Hail Mary prayer is quite long, the expression means “in a jiffy”. If you’re running late, you might say (in Italian) “I’ll be there before you can say a Hail Mary”, which is equivalent to “I’ll be there before you know it”.

That way, the reader knows what Vadi said, and also what I think he meant, where it might not be clear. This is very different to the modern English meaning of “Hail Mary”, which is a desperate last-ditch attempt.

You may also come across a word or expression that you can’t translate because you can’t find it in your various dictionaries. In many historical martial arts translations, the common practice is to throw in a word that might be right and hope for the best. A hail mary translation, if you like. But best practice here is to translate as much of the sentence as you can, and leave the untranslated bit in square brackets. Such as in this line describing the guard bicorno, in the Getty ms:

Questa e posta di bicorno che sta cossi serada che sempre sta cum la punta per mezo de la strada.

I translate this as “This is the guard of two horns that stands so closed that it always stands with the point in the middle of the way.”

Let’s say “serada” was unknown. Then it would read: “This is the guard of two horns that stands so [serada] that it always stands with the point in the middle of the way.”

It is perfectly alright to publish a translation with a few mystery words in it, so long as you’ve done due diligence to find them out. If they are commonly understood by native speakers, or easily found in a proper dictionary, then your reader will understandably lose faith in you.

It is common practice to leave some words untranslated, especially technical terms. As the translator, it’s your job to make judgement calls, and this is one of them. Some translators translate everything. Some leave far too much untranslated, rendering the translation useless to the reader. When I’m translating, I have my students in mind. What do they need? What do they already know?

So I often leave technical terms that we use in class all the time untranslated. This includes the names of blows (mandritto fendente for example), and the names of guards, and the names of certain techniques (colpo di villano, for example).

But I don’t do this the same way in every book. In a training manual aimed at practitioners, I’ll leave the terms untranslated throughout, and define them only on the first use. The students are supposed to learn them. But in a book billed as a translation (such as From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice), I’ll translate everything (as you see in the punta falsa and bicorno translations above).

However a lot of words that appear to be technical terms wouldn’t appear so to a native speaker, and it’s critically important that the target reader gets what they need, so I think it’s better to err on the side of translating everything.

Translation layout

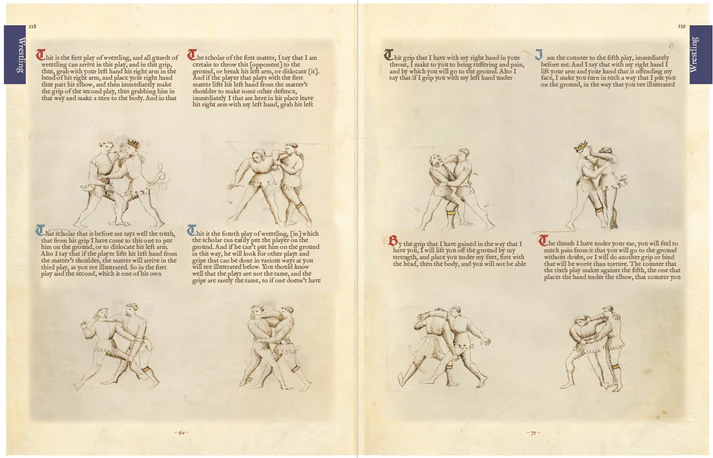

Wherever you choose to fall on the analogous translation spectrum, you have choices about how to present your work. If there are large chunks of text with no illustrations, you have the following options:

Reproducing the layout of the original. This is excellent for making a version of the original text that’s simply more accessible to the reader. The trickiest part is the page breaks, where you have to decide where exactly in the sentence you make the break.

Side-by-Side with the original. This can make it even easier for readers to find which bit of the translation applies to which bit of the source, but will often compromise the layout of the source. The team at Freelance that produced The Flower of Battle went with this option, sacrificing the page layout of the source, but presenting each page with the transcription and translation in about the same place as on the facsimile.

Side-by-Side with the transcription. This is great for readers trying to learn to work with the original source. You can break up the transcription into paragraphs or even sentences, to make it even clearer. I used this for my transcription and translation of Fiore’s introduction to the Getty ms, in my From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice: the Wrestling Techniques of Fiore dei Liberi.

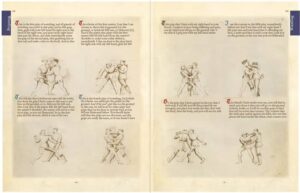

Where you have images, you must make it absolutely clear which image your transcription and/or translation refers to. Many sources simply have one image per page, which makes things quite simple. But where you have multiple images per page, you must arrange the transcription/translation so that it is crystal clear which image the text refers to.

Using other people’s transcriptions and translations

You have to be very careful about copyright, and giving credit, when using somebody else’s work. If you are going to quote more than a few lines, you absolutely must have permission from the rights holder. In some cases, the work has been published under copyright terms that allow for unlimited non-commercial use, in which case have at it, just give credit (whether it’s required or not).

In most cases, you need permission from the publisher. I always check with both the author and the publisher, assuming I can get hold of both.

This is true regardless of the format you are using. For instance, I checked with Reinier van Noort before quoting his translation of Johan Georg Pascha’s jaegerstock material in a series of jaegerstock videos I was doing.

My quotation of the few lines of Leoni’s translation above falls squarely within fair use, but as a matter of courtesy I let the publishers know. It’s always better to be open about what you’re doing, and to give more credit than is strictly required.

It’s very common for HMA researchers to use other people’s translations. Translation is hard, and you may not have the language skills to do it yourself. There are some drawbacks though:

- You may have no way to know how accurate the translation is

- You may be using an out-of-date or inaccurate version

- Every translation is also an interpretation, so the translator may be coming from a completely different point of view, or have unfortunate ideas about how swords work that lead them to translate things incorrectly

- You have no right to use the translation without permission unless explicitly stated (which is unusual)

- You have no right to alter, correct, or change the translation, even if you find a mistake. You have to quote it precisely, and add any corrections in the commentary or footnotes.

I think that a professional instructor is morally obliged to be able to work with the original source in its original language. You simply can’t trust somebody else’s translation, unless you are able to at least check it yourself. But it would be absurd to require amateurs to master a long-dead dialect of a foreign language before getting to work on the interpretation.

Just be aware of the pitfalls.

Incidentally, the reason I only teach from sources in English, Italian, Spanish, French, and Latin, is because those are the languages I can reasonably work in. The only foreign language I would publish a translation of would be Italian, but my skills in the other languages are at least sufficient to have an informed opinion about the translator’s choices. If you’ve ever wondered why I don’t publish work on German medieval combat, this is the reason.

Interpretation and Commentary

So far this has been fairly simple. There are tried and tested ways of presenting transcriptions and translations. But presenting your physical interpretation of the actions in the source takes us to relatively uncharted territory. There is no established academic model to follow, so I have created one. We should start with the questions your introduction should answer.

Interpretation introduction

- What book or other source are you translating?

- What versions of the source exist, and why have you chosen this one?

- Where can that source be found?

- Who wrote it?

- What do we know about the author?

- What images do we have, and are you reproducing them?

- Are you intending the reader to actually reproduce your interpretation?

- If yes, what equipment and prior training will they need?

- If no, have you provided other resources for readers who want to have a go?

- Who are you and why should the reader trust you?

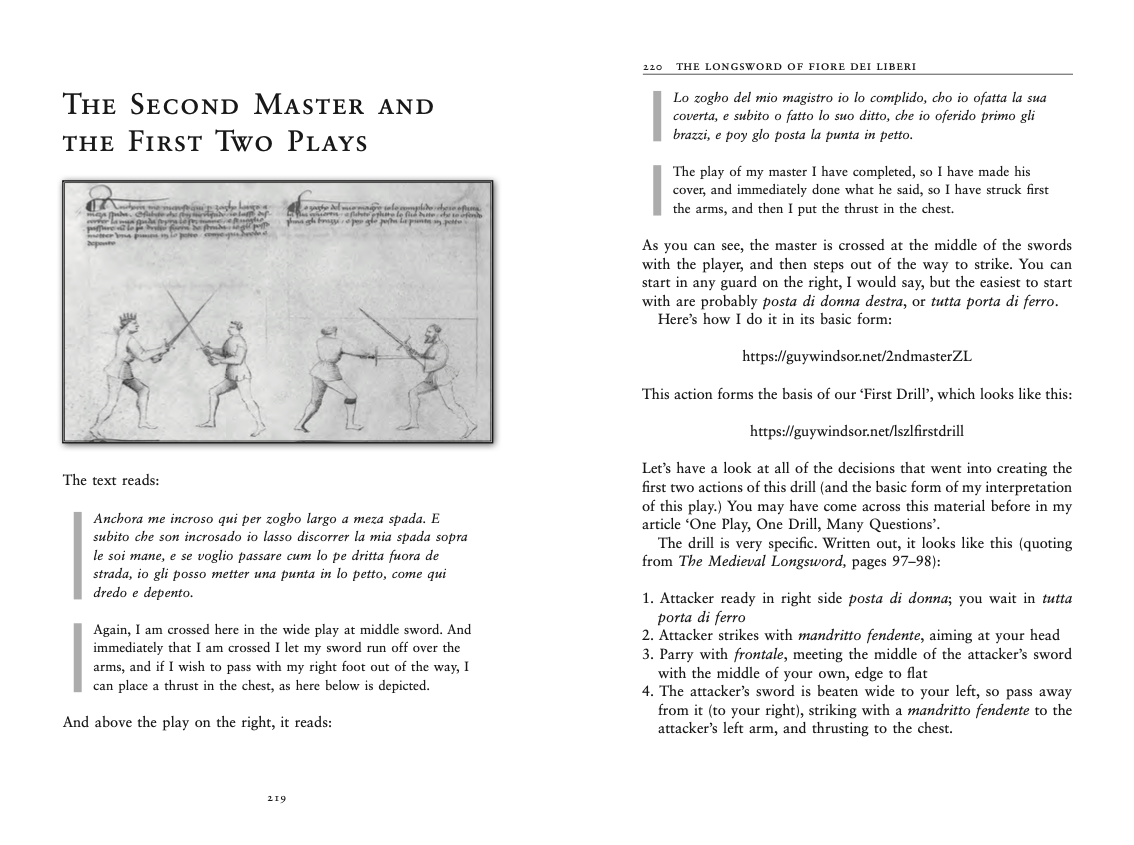

Interpretation layout

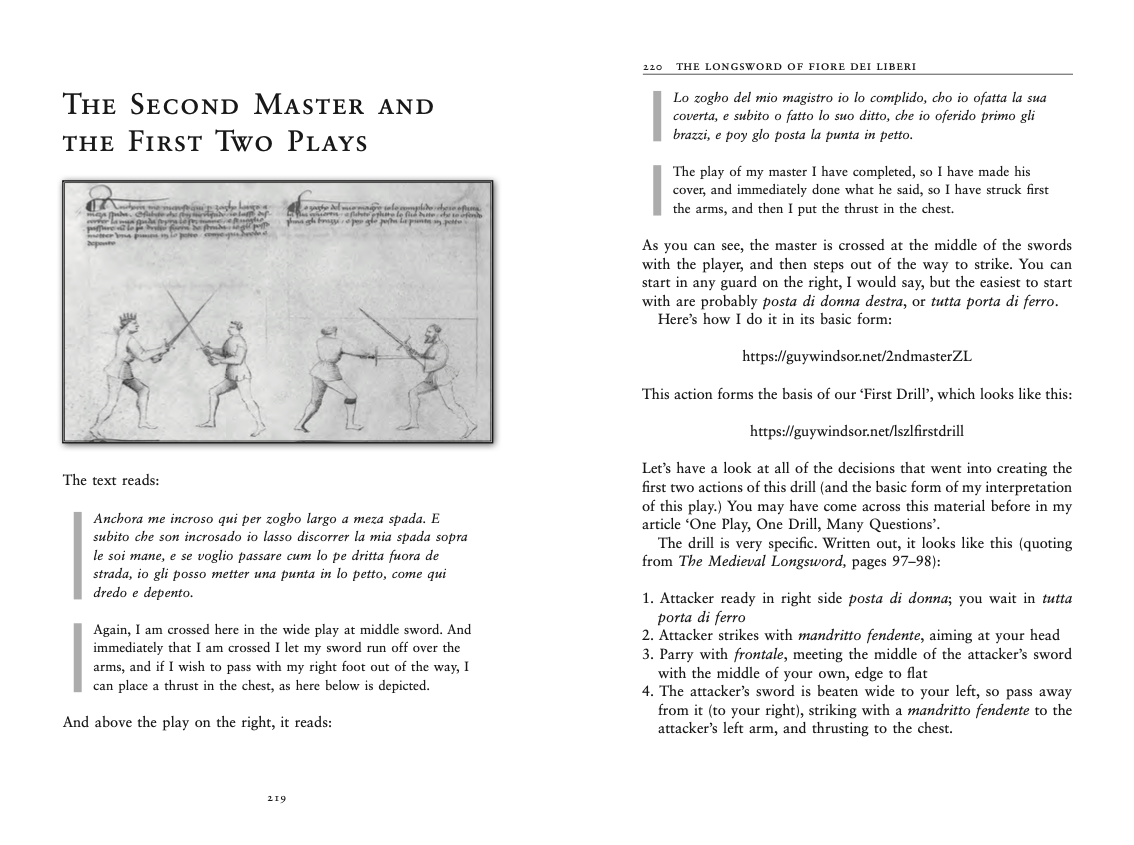

Here is the ideal layout for presenting your interpretation:

- Source image where available.

- Transcription of the text if necessary.

- Translation of the text if necessary.

- Commentary on your translation and the play it represents.

- A blow-by-blow description of your interpretation.

- A video clip of how you enact that interpretation.

If you follow this format, people can see what you are basing your interpretation on, and why. They may agree with you 100% right up to the video clip. Or they may see an error in your translation that affects everything downstream from there.

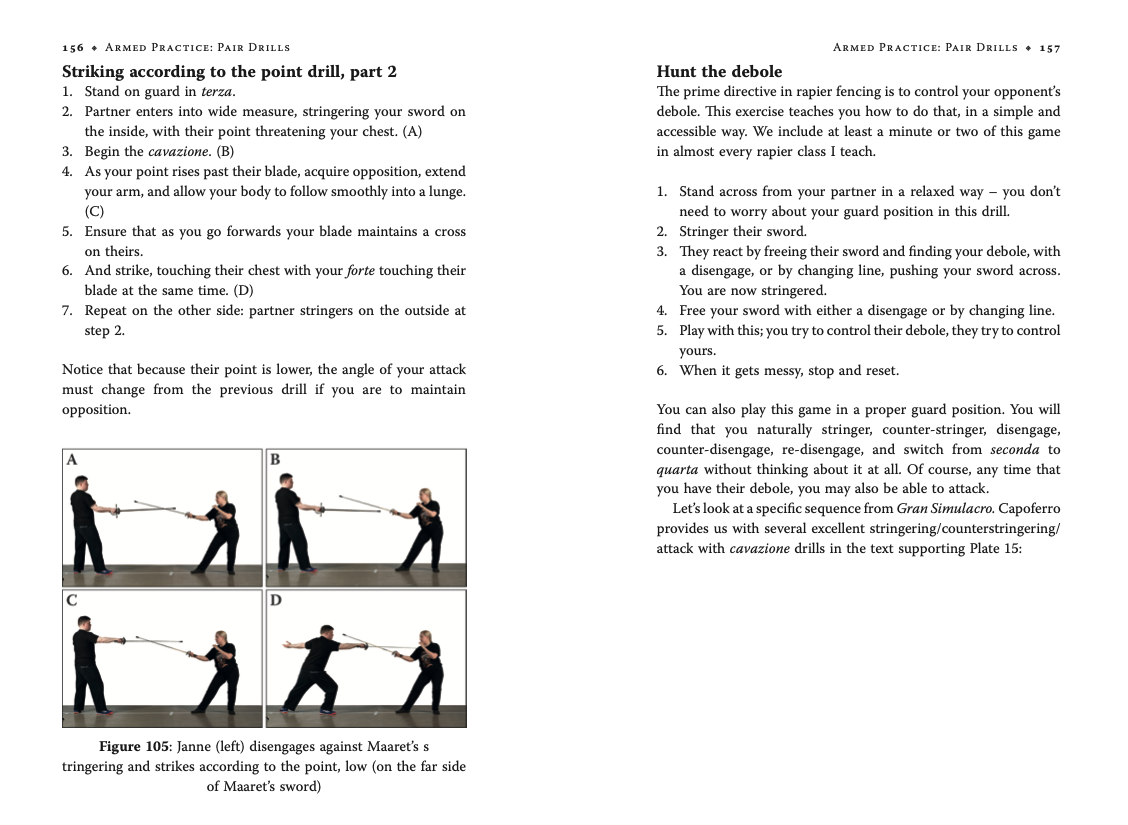

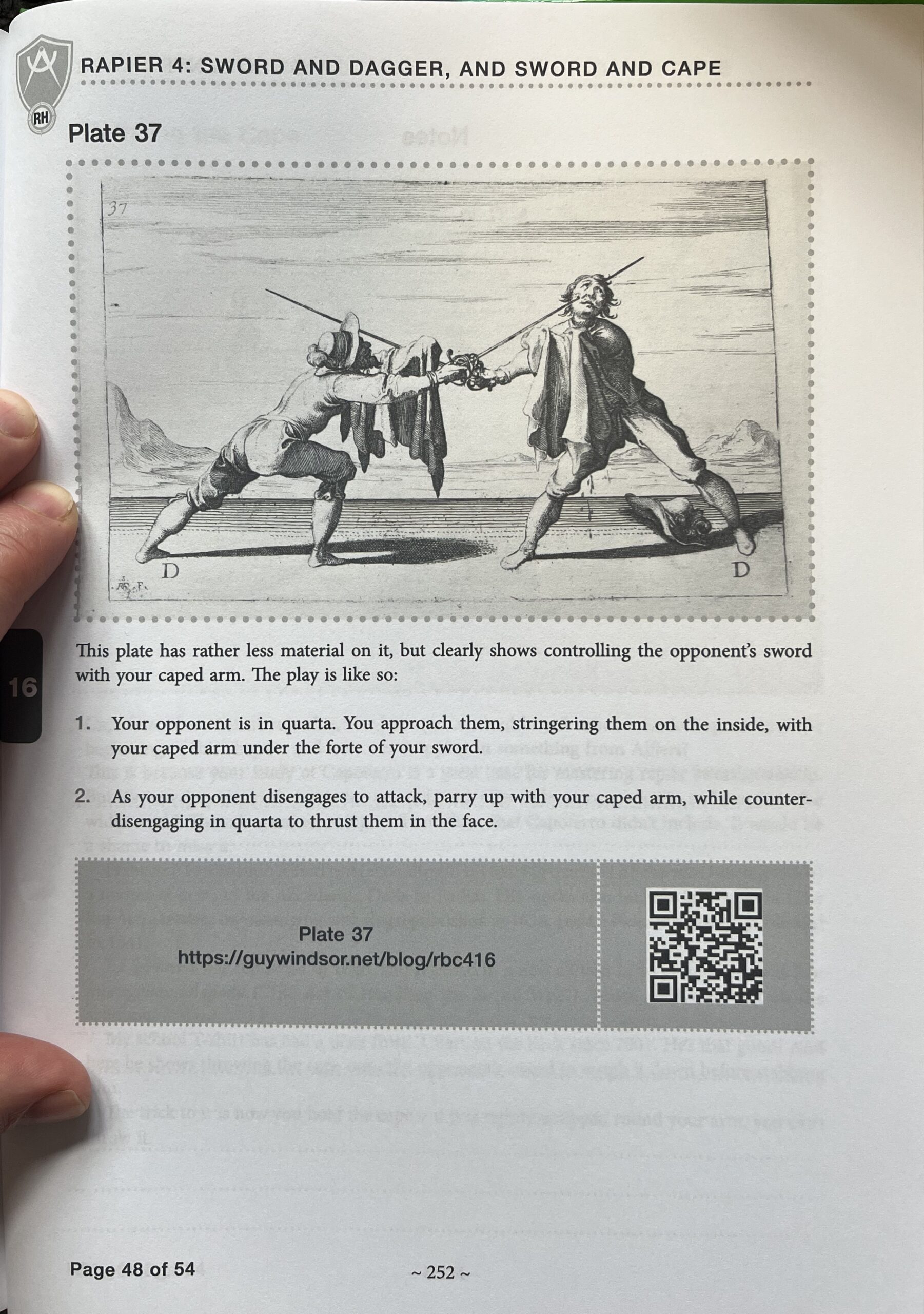

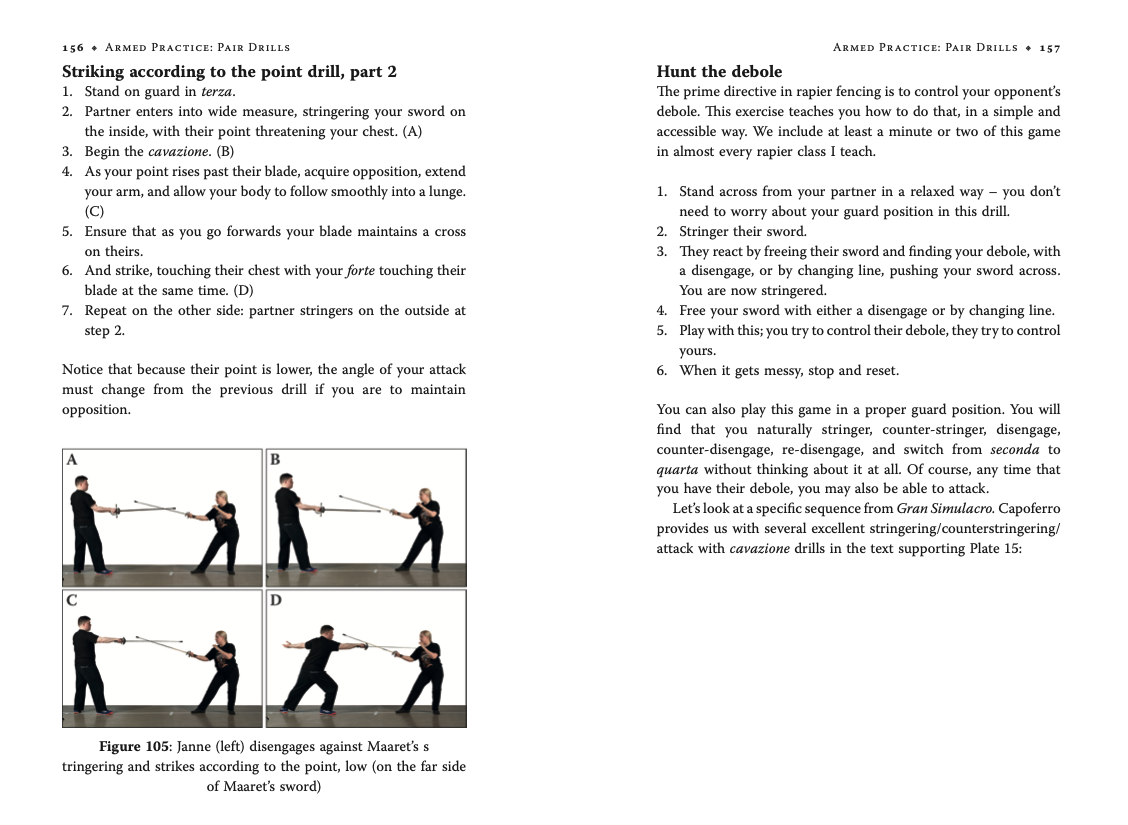

You can see how this looks on the page here:

You may need to go into some depth and detail about a concept, rather than an action. In that case, it is best to separate that out into its own chapter. In From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice, I have a 13 page chapter on what largo and stretto mean, and conclude each section (such as the sword in one hand, or the plays of the zogho largo) with a chapter on how the plays fit together.

It’s necessary to separate these things out for three reasons:

- It makes it easier for readers to find

- It maintains the distinction between theory and practice

- Your physical execution is ‘what’ and ‘how’. The theory explanation is about ‘why’. It’s clearer to keep these separate.

For the blow-by-blow description, I would suggest using the same format as for teaching drills in a training manual, with the prerequisites clearly stated, and the actions carefully ordered into a numbered list. Here’s a sample from the second edition of The Duellist's Companion.

Creating video clips

Let the text do the work of explaining the ‘why’ of your interpretation. It’s simply miserable to sit through a video of somebody trying to explain why they do an action a certain way, unless it has been carefully scripted and beautifully produced. The video’s purpose is to show the action. If the clip is more than a minute long, you’re talking too much.

Set up a camera on a tripod, make sure there’s enough light and you’re in shot, and just record you and whatever training partner may be required doing the action. Record it from both sides (so, you facing right, you facing left). Edit out everything that isn’t clean or necessary.

You can add title cards and end cards too. This is a good idea if you plan to release the videos publicly, so people watching have an idea of why you’re NOT TALKING. And you can advertise your work to them. Your title card text should include:

- The name of the project.

- Your name and the name of any assistants

- The name of the specific action you are doing and where it comes from

- The date you shot the video (in case your interpretation changes later)

- My video clips are usually extracted from my online courses, so I also credit the course at the end. That also tells people who like the interpretation and want to be taught how to fence with it where to look for instruction.

You now have a video example of your interpretation of that specific action. How do we embed that into the book?

Embedding video clips into your work

It is tempting to just produce the book as a very large PDF, with the video clips embedded in it. Don’t do that. So many people will tell you it didn’t load, or doesn’t work, that you’ll spend far too much time answering emails and not enough time swinging swords. Instead, the best approach is the following:

- Upload your clips to an online hosting service. I use Vimeo, but you can use a free service if you don’t mind advertising other people’s stuff.

- Create a redirectable link that is easy to type, and paste the clip’s address as the target. I use PrettyLink, through my website hosted at guywindsor.net. So every link is guywindsor.net/somethingeasytotype and points to the specific video clip I want.

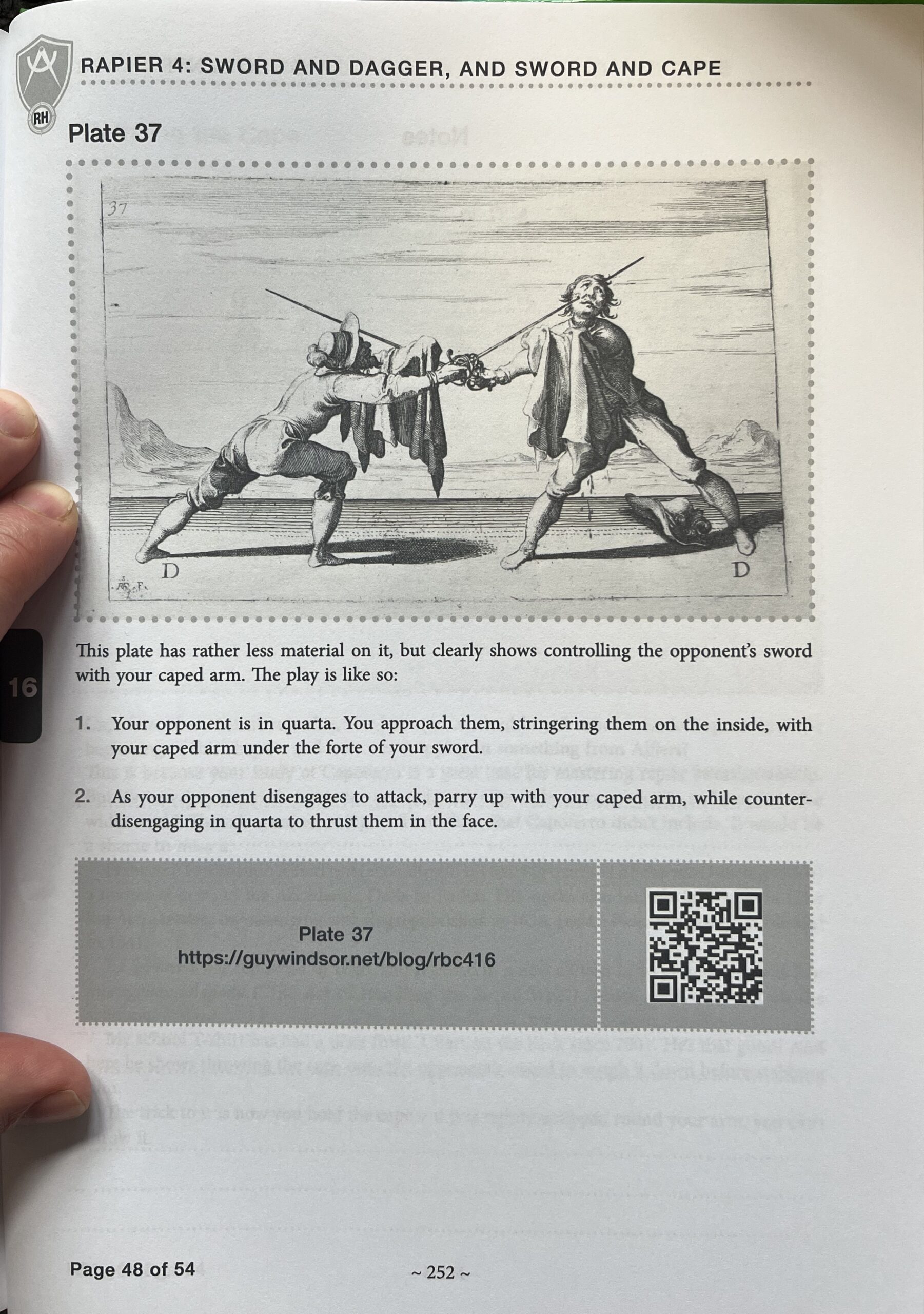

- For academic content, that is sufficient. But for training manuals and workbooks I also use a free online tool (easy to find with basic search skills) to create a QR code of the link, and include that in the book. Here’s an example from my Complete Rapier Workbook:

It is critically important to use the redirectable link. Do not ever just use e.g. a YouTube link. Unless you own YouTube and can therefore control what happens to it. The point is to future-proof your book. If I change the way I do an action, or create a better video, I can upload it somewhere, and go in to my website’s dashboard and redirect the link. If my Vimeo account was suddenly destroyed, I could upload the clips somewhere else, and redirect the links.

Using Photos

I highly recommend hiring a professional photographer if you can possibly afford it. It is really hard to take print-worthy photos without high-level gear, and without high-level post-production. You may have students, friends, or colleagues with a serious interest in photography, in which case by all means let them help. But be aware of what you’re asking for. The weekend it takes to pose and shoot a book is perhaps a fifth of the time needed to do the post-production.

Clarity is the watchword here, as always. Don’t go for artistic, don’t go for fancy. Make the photos crystal clear, and at a resolution that allows you to print them as large as possible. Shoot on the plainest background you can find, not the prettiest.

Do not insert the images in your text file. It will make the whole process horrendously difficult. Instead, name your pictures in a sensible way, and insert an instruction to layout, in square brackets, like so:

[pic: Getty fol 6v 4 4th play]

That tells me that it should be an image from folio 6v of the Getty MS, 4th image on that page, which happens to be the 4th play of the Abrazare.

If you have hundreds of images from a photoshoot, you might just go with the automatic image numbering from the camera. That’s fine, so long as you are very strict about getting the right numbers in the right place. I copy and paste the file names rather than typing out digits.

This way, even when your layout designer has no idea about your subject, if they can’t find an image, or they put the wrong image somewhere, you can find the correct image easily. Do not try to number your images in order (figure 1, figure 2 etc.) because you will end up having to redo the numbering many times as you edit the text. If you want figure numbers, put them in at the very end, after the first layout draft has been done.

For showing actual movements, I use video clips. Unless you are writing a training guide for videography, the video just has to be clear. Shoot it in the highest resolution you can, and edit it as short as you can make it without losing the necessary detail, and you’re done. The point is to replace the need for photos, not to create instructional videos.

Adding a Glossary

Are there any terms a lay reader may need to look up? If there are six or more, I’d suggest including a glossary at the back of the book. Such as my Academese glossary, reproduced here:

Academese Glossary v.1.02

Citations and Bibliography

Your research will no doubt refer to other people’s work. The modern standard is for in-line citations. This works by simply putting the author’s name, the year of publication of the source you’re citing (if necessary- see below), and the page reference in brackets, in the sentence or immediately after a quote. For example:

Guy’s completely erroneous interpretation of Fiore’s sword draw (Windsor 2018, 52) sets the seal once and for all on his reputation as a complete turnip-head!

Or:

Questo zogo sie del magistro che fa lo partito qui dinanzi. Che segondo chello ha ditto per tal modo io fazo. Che tu vedi bene che tua daga tu no mi poy fare nissuno impazo.

This play is of the master that does the technique before this one. I do it in the way that he has said. You can well see that your dagger cannot cause me any trouble. (Windsor 2018, 52)

Note that I indicate the quotation with a change of text formatting. Whatever you do, make it abundantly clear what you are quoting, and exactly where your reader can find it.

Bibliography

What books have you referred to in your book? List them here. I usually divide them up by type, then organise by author’s last name. Include the author’s full name, the title of the work, the publisher, and the date published. Such as:

Windsor, Guy. Mastering the Art of Arms, Book 1: The Medieval Dagger. Freelance Academy Press, 2012.

Windsor, Guy. Mastering the Art of Arms, Book 2: The Medieval Longsword. The School of European Swordsmanship, 2014.

The date is especially important if the author has more than one book in your bibliography. That way when you are citing them in your text, you can use the standard in-line format, for example (Windsor 2012, 147) which means page 147 of the book this Windsor chap published in 2012.

If they only have one book in your bibliography, you can leave out the year. Such as (Windsor 147).

If they have produced more than one book in the same year, then format it like so: 2018/1, or 2018/2 etc.

Other Things to Include

These are less critical to making your research available, but they are good practice to include. Your work should have an acknowledgments section, a list of your other works, and some biographical information about you. I summarise this like so:

Acknowledgments:

Who helped you learn this stuff in the first place, and to produce the book?

More books by Guy:

If they liked this one, they may like the others.

About the Author

Who am I, and why should you listen to me?

How can they find you online?

And how can they get on your mailing list? [top tip: you can get on my mailing list with the form at the bottom of this post]

Publishing and Distribution

There is no sense in putting all this work into writing up your research if nobody ever reads it. So you need to make some decisions about distribution. Let’s start with copyright.

Copyright options

As the author, your work is automatically protected by copyright law. But, you have various options available to you whether you want to give it away, or get paid for it.

If you want to sell your work it is not strictly necessary but still a good idea to register your copyright. This can be done through various agencies. I use protectmywork.com.

If you publish your work yourself, then you don’t need to get anyone’s permission. If someone else publishes it for you, then you will need a contract with them that licenses your copyright to them. Freelance Academy Press has licensed the copyright to my book The Medieval Dagger for English language only, paperback and ebook only, worldwide distribution. I have the rights to the hardback and to foreign language versions. This is why you can find a German translation of the work, and you can only get the hardback from my online store (swordschool.shop), not the paperback or ebook.

Releasing the work for free can be done by simply stating your terms in the form of one of the creative commons licences. You can for instance allow:

- Free use to anyone for any reason, with no need to credit you (CC0)

- Free use to anyone for any reason, but you want credit (CC BY)

- Free use for non-commercial use, but anyone selling your work needs your permission (CC BY-NC)

And there are other options, allowing for the work to be changed or not. You can find the entire list here: https://creativecommons.org/about/cclicenses/

You apply the licence you want by simply stating it somewhere in your work, with a link to the licence terms. This booklet Show Your Work, for instance, is © 2023 Guy Windsor. This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Which allows allows reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.

Note that this noncommercial licence stops other people selling the work. I can still, for instance, produce a version of the book for sale.

For free distribution, you simply need to produce the book to a reasonable standard of editing and layout (any word processing software will do that), and export it as a PDF. Then share that PDF wherever you like. I would suggest including the following, which are easily forgotten:

- Your name

- Your copyright terms

- Page numbers

- A link to your website or anything else of yours that the reader may be interested in.

I cover publishing books and marketing them in detail in From Your Head to Their Hands: how to write, publish, and market training manuals for historical martial artists, so if you are planning on producing an actual book that people can buy, please refer to that.