Ultra-geeky sword post alert: this is a lengthy and detailed discussion of some really specific terms from Fiore. Expect pedantry and nit-pickery, in the service of a definition of terms which has little bearing on how we actually fight. Read on only if that sort of thing floats your boat. I have written this because a friend and colleague asked me what I thought about ‘largo' and ‘stretto' these days. It turned out longer than I expected.

Since study began on medieval and Renaissance Italian swordsmanship, the terms giocco largo and giocco stretto have been discussed at length. The earliest reference we have to these terms is in Fiore dei Liberi’s Il Fior di Battaglia, (c.a. 1400) and they are a consistent feature of most Italian sources from then until the middle of the sixteenth century, after which they are less common.

What do the terms “largo” and “stretto” mean?

I'm going to be using the Italian terms a lot in this article, so let's take a moment to look at translating them into English. Giocco (or zogho in FdB) means ‘play’ or ‘game’. This is consistent and unremarkable, and has about the same connotations as the English word. I can’t think of an expression in either language where you might translate the term as anything else: it even works in mechanics, where slippage in a mechanism is ‘play’ in English, and ‘gioco’ in Italian. I should note that there is no connotation of measure with this term. Measure is misura.

‘Largo’ means ‘wide’, with connotations of ‘loose’, such as in the expression ‘questa giacca mi sta larga’, ‘this jacket is loose on me’, or ‘open’, such as in the expression ‘andare al largo’, ‘to go out into the open sea’. Sticking with the maritime theme for a moment, ‘off the coast of Pisa’ would be ‘al largo di Pisa’. Freedom of movement is implied, as is space to play in.

‘Stretto’ is the past participle of the verb ‘stringere’, which means ‘to constrain’, ‘to grip’, ‘to squeeze’. It has a lot of connotations, and you can see many of them at this convenient dictionary link: https://dictionary.reverso.net/italian-english/stringere There is no one perfect English equivalent. Stretto as an adjective is ‘narrow’ or ‘tight’, such as in the expression ‘questa giacca mi sta stretta’, ‘this jacket is tight on me’, with the implication of restricted movement. To return to the maritime theme: ‘una stretta di mare’ is a ‘strait’, a narrow channel of water between two pieces of land. It’s worth noting that it’s only used to indicate ‘close’ in phrases like ‘un parente stretto’, ‘a close relative’. Close would normally be translated as ‘vicino’. The single English word that best fits the set of meanings is “constrained”.

While these examples are modern, there is no reason to believe that the meanings of these words have changed over time; I’ve tried to find evidence that they may have, and failed. In modern HMA parlance, the usual translations used are ‘wide play' and ‘close play'. Neither is particularly apt; ‘loose play' and ‘constrained play' would be better, but there's little chance of changing them in the wider community after so long. But bear the connotations in mind.

For most of the time since we began studying these sources, most people have translated and interpreted them to mean ‘wide play’, as in fencing from far away, and ‘close play’ as in getting to grips; in other words, the defining feature is measure. I published this theory myself in The Swordsman’s Companion in 2004. Many of my colleagues (excellent people all) still hold that opinion, which you can read a full discussion of in Greg Mele's article here. The article is explicit: “Zogho Stretto (close or narrow play) is the measure at which dei Liberi…”

For the last decade or so I have held a more nuanced view of their meanings. I’ll confine my interpretation remarks to Fiore, as that’s where the most disagreement lies, and also where I have the most experience and expertise. And I’ll include here all my published opinions on the subject, so you can see how they have developed over time. Before I get onto this, I should be clear that the ambiguities occur only when discussing the sword; all abrazare and dagger plays are considered ‘stretto’, and the grappling plays of the sword mostly occur in the ‘stretto’ section. On this we can all agree.

Where we disagree is the notion that the term ‘giocco stretto' is effectively synonymous with ‘misura stretta' (which in Capoferro's Gran Simulacro at least is the measure at which you can strike without passing, which we might indeed call ‘close measure').

How do the terms largo and stretto apply to our practice?

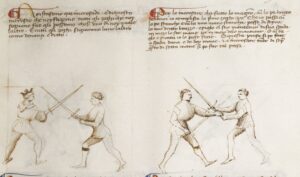

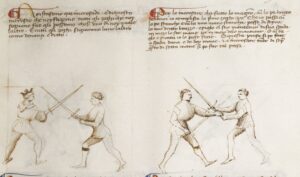

As I see it, in Fiore's plays, the defining tactical consideration (and the organising principle of the longsword section of his book) is the crossing of the swords, in which the measure is approximately the same, but the blade relationship, and so tactical situation, is quite different.

This gif illustrates the point nicely:

These are the three crossings from the Getty ms, centred on the front foot of the player. The outstandingly obvious conclusion is that the measure seems pretty much the same, but the blade relationship changes hugely. (With thanks to Joeli Takala who made a gif like this in 2010, which I reproduced because the original stopped moving.) There is no question that one of the two crossings shown at the middle of the blade is ‘zogho largo', and the other is ‘zogho stretto', as they are the first images from those sections. From one, we are free to strike, from the other, our best course is to enter with a pass ‘and come to the strette'. [I know that some researchers consider the images to be unreliable, but in my experience they are almost invariably very accurate. And once you start playing the ‘but the drawings aren't photos' card, you might as well discard all the pictures altogether, because it opens the door to making the images say whatever you want them to.]

So as I see it, “zogho stretto” is a tactical condition of the play, to which our best response is to enter in. Zogho stretto in general is ‘the condition of play in which you are constrained and cannot strike directly”, and zogho largo in general is “the condition of play in which you are free to strike”. “Le strette”, “the constrained ones”, is the term for techniques in which we come to grips. Yes, they are done from closer in than the “unconstrained plays”, but to say that they are defined purely by their measure is wrong; they are defined by being grappling actions.

That's the short version. I shall now expand at considerable length…

Further depth and detail on largo and stretto

Back in 2009, I published an article that described my new understanding of largo and stretto, and includes an analysis and interpretation of all of Fiore's longsword plays out of armour. Please read it, and then we'll move on… you can download the pdf from here:

Crossing Swords 2009

Back again? Excellent.

Recall this passage:

It is my contention that zogho largo, wide play, describes the actions that are safe to do when the attacker’s point is driven wide. Zogho stretto, close play, describes the actions that we must do if the attacker’s sword is too close to us when we are crossed. The correct action then is to pass with the cover (i.e. without leaving the cross) and execute one of the close play plays.

As the defender, one should not seek out the close play; as Fiore states, from the stretto cross, either person can do the plays that follow. But by passing in, we prevent the attacker from winding the point into our face.

My interpretation of the basic form of these plays as it stood in 2009 can be seen in these videos:

Sword in One Hand:

Zogho Largo:

Zogho Stretto:

My current up to date and explained in detail interpretation of these same plays are Section 8 of my Complete Medieval Longsword Course

I should point out that introducing this interpretation of largo and stretto did more to prevent double hits in freeplay in my school than any other change to the way we conceptualise Fiore's art. Suddenly, people started paying much more attention to whether an action was appropriate in the context they found themselves, simply because they now had a way to define that context.

By 2014, my thinking had not changed particularly, despite my colleagues’ best efforts to persuade me that it was all about measure: in my book The Medieval Longsword, pages 43-45, 2014, I wrote:

Perhaps the most overt tactical distinction Fiore uses is between zogho largo, universally translated as “wide play”, and zogho stretto, which may be translated as “close”, “constrained” “narrow” or “tight” play. I find “constrained” to be the most accurate rendering, but “close” is currently the most common choice. This topic has produced perhaps the most persistent and widespread disagreement amongst Fiore scholars, so I will go into some detail regarding what I think these concepts mean, and how I use them.

Fiore’s plays of the sword in two hands are clearly divided into the 20 plays of the zogho largo and the 23 plays of the zogho stretto. There are also plays done with the sword in one hand, in armour, and on horseback. The distinction between, say, the plays of the sword in armour and those of the sword on horseback are pretty obvious. The distinction between what constitutes zogho largo and what constitutes zogho stretto has been far less clear. In my first book, I defined the terms gioco largo (wide play) and gioco stretto (close play) as functions of measure: when you are close enough to touch your opponent with your hand, you are in gioco stretto. If you can reach him with your sword using one step or fewer, you are in gioco largo. This is a useful distinction to make, especially when classifying and cataloguing techniques.

For many years, this stood as the standard interpretation of zogho largo and zogho stretto, however, this is clearly not how Fiore uses the terms. (Remember our earlier discussion of changes in interpretations? Here you can see my pressure-test system in action.) In il Fior di Battaglia, we clearly see actions done close-in but placed in the zogho largo section (such as the 14th play of the second master), and actions done from quite far away placed in the zogho stretto (such as the 12th play). So what, then, do “wide” and “close” play refer to?

Simply put, the relationship between the two swords when they cross. There is a plethora of circumstances in which you are free to leave the crossing and strike as you will—these are all considered “largo”. In other circumstances the conditions of the bind are such that if you leave the crossing you will immediately be struck. In these cases you are constrained to enter in under cover, and use one of the “close plays”.

In practice, the type of crossing that demands close play is very specific: you must be crossed at the middle of the swords, with the points in presence (i.e. threatening the target) and sufficient pressure between the swords such that if one player releases the bind, he will be immediately struck. Ideally both players have their right foot forwards, which makes it easier to enter in. This is a situation of equality, in which either player should do the close play techniques.

In all other circumstances, most commonly when the opponent’s sword has been beaten aside, it is safe to leave the crossing to strike your opponent. This is the fundamental condition of wide play. If it is necessary to maintain contact with the opponent’s sword and enter to grapple or pommel strike, you are constrained to the close play. So, the plays are ordered according to the kind of crossing that they follow. These conditions exist in a continuum. As the opponent’s sword gets closer, and the bind gets firmer, your ideal response changes. As it switches from “leave the bind and strike” (largo) to “keep in contact with the bind and enter” (stretto), so you will find your ideal response in one section of the book or the other. Identifying these conditions is perhaps the key tactical distinction to make in this system. Note that close play techniques can often be done in a wide play situation, but wide play techniques cannot be done from a close-play crossing without extreme risk. The techniques we see in the 10th, 14th, and 15th plays of the second master of the zogho largo (crossed at the middle of the swords) section are clearly “close”, and there is no practical distinction between for example the 10th play here and the 2nd play of the zogho stretto. It’s apparent then that we have a choice: either Fiore organised his book as a catalogue of techniques arranged by the measure in which they occur, with several errors, or ordered them according to the tactical circumstances in which they should be done, with no errors. Which would you choose?

As a rule of thumb, if your opponent’s sword is moving towards you, or pressing in, you must bind it to prevent it from hitting you (stretto). If it is moving away from you, you can simply strike (largo).

Wide and close play describe what happens, but can also be used to describe a set of tactical preferences, an approach to the fight. When fencing an opponent who is much more comfortable in wide play, we may engineer a situation where only close play techniques will work. We can also of course deny a close-playing opponent the context he wants, and slip away into wide play as he tries to constrain us. A good fencer will be comfortable with both contexts, though most people have a preference for one type of play or the other.

This interpretation is still my default, though I would express it differently now. In short, you are in ‘wide play’ when you are free to leave the crossing to strike, and in ‘constrained play’ when you have to maintain contact with your opponent’s sword to strike.

So where do I stand now?

The defining features of largo and stretto

In combat, you are only likely to have your freedom of motion constrained by some threat or physical contact from your opponent. When it comes to making decisions under pressure, it’s usually unhelpful to have more options than necessary, because every choice slows you down. So I think the point of the largo-stretto distinction is to reduce the likelihood of getting hit by making it as clear as possible when it is safe to strike. It’s a tactical distinction, not a technical one. The tactical situation is determined by the following conditions:

Measure: how far apart are you? Yes, measure is a critical component of the condition of play, but not its defining feature.

Movement: where is everything going? Is your opponent pushing in, pulling back, binding strongly, yielding? And you?

Blade relationship: are the blades crossed, and if so, how?

I’ll expand on these one at a time:

Measure:

If you are in range to strike without stepping, this distinction is crucial. Are you free, or constrained? Outside that measure, it’s irrelevant. Fiore does not explicitly discuss measure at any point- the term is used once only, on the segno page under the lynx: E acquello mette sempre a sesta e a misura. Clearly, if he had wanted to define the plays of the sword by their measure, he had the linguistic tools to do so. We can see that at the moment the swords cross, the measure is approximately the same in all three crossings, and it's at the moment of the crossing that tactical situation is defined. To be in either largo or stretto play, you must be close enough to strike.

Movement:

The measure and the blade relationship will normally be in constant flux. Sword fighters rarely stand still when this close together. The exact positioning of the players at a given moment is less important than the direction they are moving in. If your opponent’s actions are such that you have to bind their sword, you’re probably in a stretto situation. If they are moving away from you, then you are probably freer.

Blade relationship:

Is your weapon controlling your opponent’s? If not, it should be.

Let me quote again from The Medieval Longsword pages 159-161

Whoever masters the crossing, gets the strike. All medieval swordsmanship sources emphasise what happens when the blades cross. This crossing can be reduced to three critical factors: where on the blades the cross occurs, where the points of the swords end up, and how much pressure is being exerted. Up to now, almost every parry has been aimed middle to middle, and has worked as intended, beating the sword aside, with the exception of the “sticky” cut against the position of the sword in one hand. This was by way of introduction to the idea of binding the sword, which is a process of gaining mechanical control of your opponent’s weapon using your own.

In combat, the crossings of the sword happen so fast, and ideally last for such a short time, that it is unusual to respond to their specific conditions as they occur; more commonly, cues in our opponent’s prior movements indicate what will happen when the blades meet. It is nonetheless useful to analyse the possible crossings, to get an idea of what may occur and what you should do about it. This section is a bit like explaining traffic lights to a driving student.

Let’s start with where on the blades the cross is made. Most of the time you would be aiming for a cross at the middle of both swords, but Fiore divides the blade (as we have seen) into three parts: the tutta spada (the first section near the hilt), the mezza spada (the middle section) and the punta di spada (the last section, near the point). Mathematicians will have no difficulty working out that there are nine possible combinations of places on the sword where the crossing happens:

We must also consider the position of your point, close enough to be a threat, or wide, and his, close or wide, so multiply 9×4 and we get 36 possible crossings. Add to that (or rather multiply) the degree of pressure between the blades (let’s be binary and say strong or weak—we could have a dozen gradations of strength) and we have 72 crossings. And lastly, which side is open—inside, outside or neither? So multiply by three and we get 216 possible meetings of the swords. That is patently absurd. Let’s carve it down a bit.

What matters most is what you can do from a given relationship of the blades. In practice, it is only possible to apply pressure when meeting at the mezza or the tutta of your sword. So where there is a punta involved, that sword (or both) are always weak in the bind.

Also, when crossed at the points, the points of the swords can’t be threatening either of you directly, as you are either too far away, or they are pointing up or to the side, so it can always be consid- ered “wide”. Likewise, when crossed at the tuttas, the points must be wide, or there would have been a strike already, you’re so close. Where one point is against another’s mezza or tutta, there should be sufficient leverage advantage that the punta is always weak in the bind, and will be driven wide. So, that same table now looks like this:

It should go without saying that you strike on the side he is open; if you aren’t sure, if neither side is clearly open, go to the other side (so if your sword is on the right of his, go to the left). This is because whatever force he is using to keep you out of the centre should open that line when you release your counter-pressure.

The only part of the table where there is any real ambiguity is the middle one, where the swords have met in the middles: the points may be wide or close, and the bind may be strong or weak. If his point is close, and the bind is strong, you must enter into the close plays. This crossing leads only to the zogho stretto. If his point has been driven wide, and/or there is little pressure in the bind, it is safe to either grab his blade and strike (if it is close) or just strike (if his point is wide). These are examples of zogho largo.

Largo and stretto in other systems.

And what about Vadi? Well, he doesn’t divide his 20 plays of the longsword this way, but he does refer to largo and stretto play, principally in his Chapter 3: Theory of the Sword, especially on folio 5v. You can download my free translation of the entire manuscript from here and make up your own mind… Or if you're feeling wealthy, you could buy the snazzy hardback of the whole book: my new The Art of Sword Fighting in Earnest!

For the perspective of a Bolognese fencer, Ilkka Hartikainen has an article on the terms here.

In conclusion

So let me sum up:

Being close enough to strike is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the term ‘zogho stretto’ to apply. If you are free to strike, and have room to do so, the play is ‘largo’. If you are constrained, the play is ‘stretto’. Fiore’s solution to the problem of being constrained is to enter in with a pass, to get to grips (he does love his wrestling); grappling plays of every kind are ‘strette'. It’s worth noting that we find different solutions to the same tactical situation (as shown in the crossing of the master) in the German medieval sources, which often recommend a winding action instead.

Zogho stretto is a type of play, not a specific measure. All of Fiore’s stretto plays involve grappling, which requires you to get close. But that isn’t what the term means.

This interpretation makes teaching decision making at the crossing easy. A catalogue of techniques organised by measure is not useful; a distinction of when to do what is much more so. So whether you agree with my thesis or not, you can still use the idea behind it to make better tactical decisions in the moment. I think the best thing about this interpretation is that it is directly applicable to winning fights, of which I'm pretty sure Fiore would have approved.

Further reading:

From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice: the longsword techniques of Fiore dei Liberi

The Medieval Longsword