Plastic swords are for children.

Disclaimer: this post should be read as a completely personal, utterly unscientific, non-practical, emotional, historical fundamentalist tirade against something I find offensive. On this matter I am unapologetically fanatical. You have been warned.

About eight years ago, in 2004, I was appalled to find, at a WMA event in America, the majority of practitioners using aluminium swords. When I returned home I drew a line in the sand, by posting this on Sword Forum International, under the heading Aluminium Wasters: NO!

Aluminium wasters are becoming more and more popular as longsword training tools. Two main reasons are put forward for their use:

1) Price: at about $120–$150 they are half the price of steel blunts.

2) Safety: given their thicker edge and lower mass, they impart less energy to the target on impact, so are safer to fence with at high speed.

I find this development alarming, and not in the best interests of the Art of Swordsmanship. Here are my reasons:

1) Aluminium wasters are unhistorical. There is abundant record of the use of wooden wasters, and some extant examples of blunt steel training longswords, but (obviously) no aluminium swords were used in period. That said, I use protective equipment like fencing masks and hockey pads, which are equally unhistorical, but in my view have far less negative impact on how techniques may be executed.

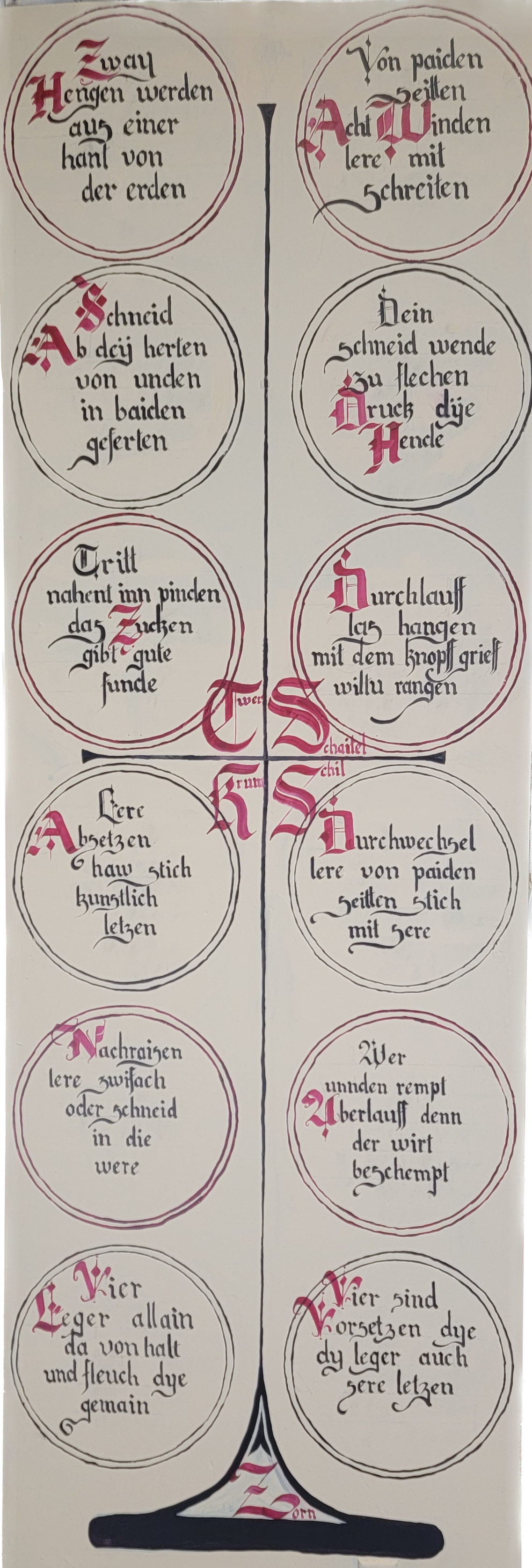

2) They do not behave like steel swords. Their handling characteristics are totally different, they weigh less, the heft is just wrong. You can spot an aluminium sword being used from across the room, simply by the way it moves. Aluminium planks resonate quite differently to tempered steel blades (blunt or sharp), so when the weapons collide, they behave totally differently (this is true for all wasters, wooden, aluminium, padded, bamboo, or whatever). Many of the more sophisticated techniques rely on the feeling of the blade contact in your hands (often called sentimento di ferro); think of mutieren or duplieren in the German school (see page 184 of Tobler’s excellent ‘Fighting with the German Longsword’); think of the difference between yielding through frontale to get to the outside, or holding your opponent in frontale for an instant while you grasp his blade and kick him in the kneecap (as one sees in Fior Battaglia). You simply do not get the same level of information coming through aluminium.

In addition, steel swords spring away from each other, or stick, depending on how they meet. This is a vital consideration when working on deflections; aluminium wasters just do not behave the same, so do not adequately prepare you for the conditions of a real fight. (Though none of us intend to fight for real, all our training, to be valid, must work as preparation for the real thing. Otherwise we can give up our pretensions to Western Martial Arts, and start developing western combat sports. Nothing wrong with that, so long as the terms are not confused. The sporting approach is death to the Art, as the history of fencing clearly demonstrates.)

3) Safety in free sparring is an illusion. Your equipment cannot keep you safe. Granted, it is less easy to hurt someone with an aluminium waster than with a steel blunt, but the risk is there. This is a wasteful shortcut to learning control, and symptomatic of the “I wanna be a knight, NOW” attitude that infects a lamentable minority of practitioners. It takes thousands of hours of hard training to learn to control a steel sword so that one may freeplay with an acceptable degree of safety. Any compromise that gets people sparring too soon is inappropriate.

4) My students all buy steel swords, and relatively soon after they start training. If they can afford it, you can. If you need a very cheap starter weapon, a wooden waster is the way to go. Historically accurate, and very cheap. Aluminium wasters are three or four times the price of a wooden waster, and half the price of a blunt. As such, they form an economic barrier to purchasing a steel sword, which wooden wasters do not. Save up a bit longer while training with a wooden waster, and you can have a proper sword.

I have discussed this issue at length with many of my colleagues in the United States, and so far have only heard one valid argument for the use of aluminium. In a litigious culture, where horrendous punitive damages may apply, a school or teacher must be seen to be making every possible safety concession, just in case there is an accident. Living in a country where any judge would say “you swing swords at people’s heads and then come crying to me when you get hurt? Get out of my courtroom!” I have no good answer to that, except education of the jury-forming general public.

This is a particularly difficult topic as many equipment manufacturers, particularly the small-time producers, have no facilities for making steel blunts, but can churn out aluminium wasters with ease. I hate to undermine their business, as these are decent people doing the community a good service; but if they turn their talented hands to wooden wasters and to safety equipment, they will hopefully not lose by it.

It is up to us as a community to seek always the best way, the highest way, not just the most convenient way, to pursue our Art. Aluminium wasters are a convenience, a compromise, and a step on the slippery slope towards sporting interpretations. They have no place in my Salle, and I wish they had never been invented.

I look forward to hearing your opinions….

This generated something of a storm, and with a whole six pages of wild opinion. I can't find the forum online, so it's probably defunct.

Going back across the pond as I do once or twice a year I have seen a steady diminution of aluminium- by WMAW 2011, I think there was one or two knocking around, and everyone had steel. My primary goal at that event was to introduce students to the difference between blunt steel and sharp- just as aluminium behaves differently to steel, so blunt steel does to sharp. Sharp swords stick, and an awful lot of period technique becomes a lot easier and more natural to do when the blades are sharp. As I said a hundred times that weekend alone: “if you haven’t done it with sharps, you haven’t done it at all”.

While this general improvement (as I would see it) has been going on in the part of our WMA community that I spend most of my time in, there has been a simultaneous shift in the opposite direction, mostly amongst those elements of the community who are most interested in creating tournaments. This has lead to the development and widespread adoption of the only training tool that is more aesthetically offensive to me than an aluminium sword: plastic swordlike objects. Are we children that we want to play with toy swords?

Other than simple disgust, my objections are the following:

1) they in no way simulate the behaviour of steel swords when they meet.

2) they in no way encourage students to treat the swords as if they were sharp

3) they in no way reproduce the handling characteristics of steel swords (they tend to be too light)

4) they encourage foolish freeplay. (This is not always a bad thing, but it is if you are trying to train correct responses for historical martial arts).

It is of course possible for two experts to use these things like swords, but they are generally used by beginners who are then lulled into a totally false sense of security, and a delusion of competence, that can only do them harm.

If you cannot afford a steel training sword, and want something a bit better than a stick to practice with, there is always the wooden waster, widely available and about the same price as the plastic monstrosity. To take those offered by Purpleheart armory as an example: Their plastic “longsword” costs $73, is 124cm, 48.5” long, and weighs 785g, 1.73lb (according to their website. I don’t have any of these things in my possession. You can pay 125 dollars for their type III also). Their (excellent) wooden wasters are $70, and are 120cm (48”) long and weigh about 950g (2.1lb). In terms of mass and dimensions, there is not a lot to choose between them, but in terms of usefulness as a training tool, one has millenia of pedigree, the other has not. One has been used by many of the greatest swordsmen in history, at some stage in their training; the other only by a few modern practitioners.

I am well aware that serious living-history buffs may find my plastic-soled training shoes, modern-pattern mask, and t-shirt-based training uniform equally appalling. I wear historical clothing and footwear for research purposes, but it is not practical for class or teaching when on any given night I may teach five different systems from five different centuries. I apologise for their suffering, and I understand it. But at the end of the day, I care about the swords, I just don’t care about the clothes.

What the argument for plastic boils down to, in the end, is lowering the short-term barriers to entry, especially to freeplay entry. They are an apparent short-cut: but as my grandma used to say, “Short cuts make long delays!”. Proponents of the plastic sword argue along the lines of cost, durability, safety, etc. But there is nothing inherently practical about the Art of Swordsmanship today. If you want self-defence, go train with Rory Miller, Marc MacYoung or someone of that ilk. Neither will recommend studying medieval combat treatises to learn modern self defence. If you want a practical battlefield art, join the army. The art and practice of historical swordsmanship should not be confused with any kind of modern combat, nor should it ever be reduced to simply playing with swords. It is not easy. It is not for everyone. And it certainly demands a much higher standard of aesthetics and risk management that you can possibly attain to by following the tupperware path. Blunt steel is already a huge compromise, which is why I test all interpretations and most drills with sharps.

Since I first posted this, I have seen two use-cases for plastic swords in adult HMA. For some clubs, getting a bunch of plastic swords is a cheap and durable way of equipping a beginners' course with a sword-like-object. Fair enough- they are generally more durable than a wooden waster. There are some occasions where you want untrained people to get to play a bit with swords, such as when giving public demos in which the public can take part. In that case, there are some very light plastic wasters that are safer for novices to play with than a wooden waster.

And of course I have no objection at all to using plastic swords to train children. They're lighter, easier to make reasonably safe, and they're durable and cheap.

But don't confuse them for a good training tool for adults. They're a step further away from real swordfighting.

) that I got at least one pommel strike in my face, and ate a sword point or two.

) that I got at least one pommel strike in my face, and ate a sword point or two.