7 Countries. 4 Continents. 6 books. Two online courses. And one really good idea (I think).

It’s kind of absurd to summarise an entire year in a single blog post, especially such a busy and yet somehow still productive year as the last 12 months have been, but I need to get a handle on what my actual choices were. It’s all very well to say you prioritise x or emphasise y, but looking back you may well find that you actually prioritised z.

It seems that this year I’ve prioritised pushing books out the door (sometimes faster than they should be), and travelling as much as I can handle. Leaving aside family travel (such as starting the year on holiday in Italy with my wife and kids, taking my wife to Porto for a weekend, and the whole family to Spain for a summer holiday, and visiting my mum in Scotland (which is a whole other country)), in 2024 I went to:

- Helsinki, in February and again in May, teaching seminars for the Gladiolus School of Arms (which I’ll be doing again in mid-January 2025)

- Singapore in April, to teach seminars for PHEMAS

- Wellington, New Zealand, in April, to teach a seminar for a friend’s club (I segued through Melbourne on my way home to catch up with friends)

- The USA: Lawrence, Kansas to shoot video with Jessica Finley, Madison Wisconsin to teach a couple of seminars, and Minneapolis likewise

- Potsdam, Germany, for Swords of the Renaissance

- Mexico City for the Panoplia Iberica, and then Queretaro for a smaller event.

That’s a total of 73 nights away from home for work trips. Damn. I’ve loved it, and will be doing some travelling in 2025, but both my daughters have major exams coming up in June (A-levels for one, GCSEs for the other), so I need to be home for much of at least the first half of the year.

Publishing

In January 2024 I published From Your Head to Their Hands: how to write, publish, and market training manuals for historical martial artists. Perhaps the nichiest book I’ve ever written, but it was there in my head in between editing drafts of the wrestling book (see below), so I got it out of my head and into your hands. See what I did there?

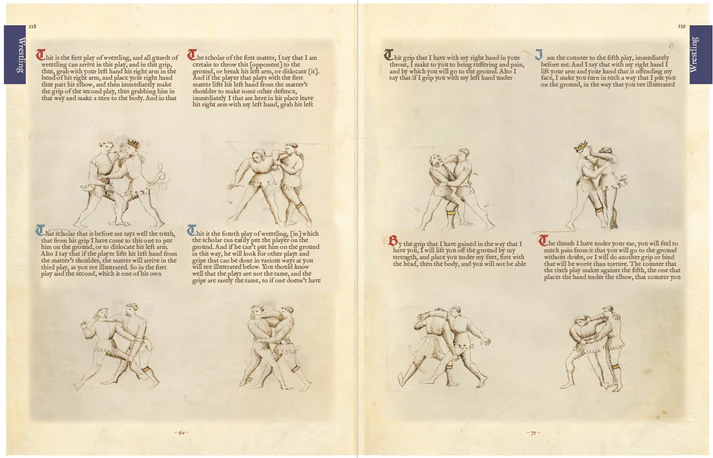

In March I published the long-awaited and technically “first” volume in the From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice series: The Wrestling Techniques of Fiore dei Liberi. Only 4 years after what will become the third volume (The Longsword Techniques of Fiore dei Liberi). It took me that long because the pandemic stopped me from going to Kansas to shoot the supporting video material with Jessica Finley. Well, that’s my excuse and I’m sticking to it. It was also just bloody hard to write.

The second volume (on the Dagger Techniques of Fiore dei Liberi) should be out in early 2025, and at that point I’ll re-cover the Wrestling and Longsword volumes and make them look and behave more like a book series.

Proof if ever you needed it that there’s no need to do things in order.

In August I published Get Them Moving: How to Teach Historical Martial Arts. This is another super-nichey book. I’m not aiming at the mass market here, just clearing things out of my head so I can get on with other things. Books do that: they simply insist on being written and published, and won’t let me alone until I’ve got them out the door.

I also managed to edit all the new material for my Medieval Dagger Course, which I had shot in Kansas. I also have a bunch of longsword material to publish, and an entire course on German Medieval Wrestling (Jessica Finley’s work).

In September I published the celebratory 20th Anniversary edition of my first book, The Swordsman’s Companion, and I’ve made the ebook free on all platforms. The book is hopelessly out of date as regards interpretation, but it’s an interesting window into the state of the art as it was in 2004. And it got a lot of people into historical martial arts.

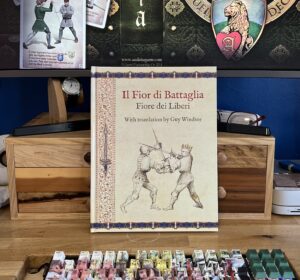

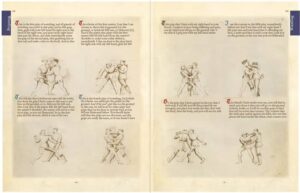

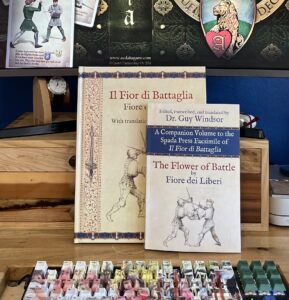

In November we published the magnificent facsimile of the Getty manuscript, with my complete translation. Unfortunately that ran into some bizarre technical problems after the first 50 or so orders had come through, so at the time of writing we are fixing the problem and reprinting the books. I also created a companion volume which includes the complete transcription as well; it’s not intended as a standalone, but it is finished and has been sent out to all the buyers of the facsimile, so I guess that counts as two more books, taking the year’s total to a somewhat absurd 6. If you consider that my first book came out 20 years ago, and in that time I’ve written and published about 18 books: a full third of them in this year alone.

Of course, publishing comes after writing, and a lot of this year’s output were mostly or at least partly written over the last few years; they just happened to be ready all at once.

My podcast The Sword Guy hit 200 episodes in December 2024, and I’ve decided to pause a while to think about what I want to do for the next 20, 50, or 100 episodes.

Business stuff

I had two main goals for 2024: to figure out how to open up my platform to other instructors, and to create partnerships with other businesses serving the HMA community. I’ve made progress on both those fronts.

Esko Ronimus’s course “Introduction to Bolognese Swordsmanship” went live on courses.swordschool.com in October this year. This is different to the collaborations I’ve done before (such as Jessica Finley’s Medieval Wrestling course) because I was not directly involved in creating it. I didn’t direct the shoot, edit the video, or take part in the production in any way. I just provided a platform to host it on, and some advice on structuring the course and marketing it. So far both Esko and I are happy with the results, and I’m open to requests from other instructors…

If you’ve bought a sword from Malleus Martialis in the past year you may well have got a discount code for one or other of my online courses, or a code to get one of my ebooks for free. This kind of thing is good for Malleus (they can offer more to their customers at no cost to themselves, and make an affiliate fee on any course sales), good for the customer (they get free or discounted stuff they are likely to be interested in), and me (I get some of the course sales money, and someone who may not know my work becomes familiar with it, and may go and buy a bunch more of my books). So if you’re in the business, and want to set something up, let me know.

Research stuff

This year there has been one significant change to my interpretation of Fiore’s Armizare: the three turns of the sword. This doesn’t change much about how we actually do things, but it affects the underlying theory behind the art, and solves a mystery that has been plaguing us for decades. Full credit to Dario Alberto Magnani. You can listen to the entire conversation here.

It also meant updating my translation of the Flower of Battle: I deleted one word. A very critical word. “Also”. Yes, it makes a difference.

Plans for 2025

I came back from Mexico with one clear vision of a problem to solve. Namely, I travel about a lot giving seminars, and so I get to see a lot of students, but only every now and then, and many of them I’ll never see again. This is unsatisfying. I don’t get to see the long-term effects of the things they have learned from me. I don’t get to see them develop over time. Of course there is some continuity, especially when I go back to teach at clubs regularly, but it’s not ideal for either me or the students.

So what to do about it? The thing that blows the students’ minds most consistently are insights into swordsmanship mechanics. Ask Leon in Mexico or Rigel in Singapore about the rapier guard quarta, and how stringering works. The look of utter startlement on students’ faces when they get it is the absolute best thing. I’m thinking about creating an online course that goes into the absolute fundamentals (ie the most important but least flashy) of how sword mechanics work, and making it free: but required for anyone signing up to one of my seminars when I travel. This will let me cover a lot more stuff in the class itself, and prepare them better to actually make use of the insights. And it will hopefully bring them more into my orbit, make them more likely to show up on swordpeople.com with good questions, more likely to come to the next seminar, etc.

I also want to create an online course on Vadi’s longsword (might as well shoot my interpretation of the entire manuscript while we’re at it), publish the dagger volume of From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice, maybe shoot the video for the armoured combat and/or mounted combat volumes, and finish The Armizare Workbook Part Two (which has been more than half written for over a year… but is still stuck in hard-drive purgatory). Part One came out in 2022, and I meant to get Part Two out in mid ’23. Oh well.

I’m planning to make all of the supporting video for From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice (so, clips of every play from Folio 1 to Folio 31v of the Getty ms) free online. They are currently only visible through the links in the books. But making them open to all should help my fellow scholars, and also provide advertising for the books. Another win-win.

The key thing to remember here is that planning is vital but plans are useless. There is no way to predict the future, and all sorts of things might get in the way of any or all of my intentions for the year. But having a think about what I want to accomplish, and why, makes it much more likely that I’ll be able to look back on 2025 with some degree of satisfaction. Let’s see what actually happens…