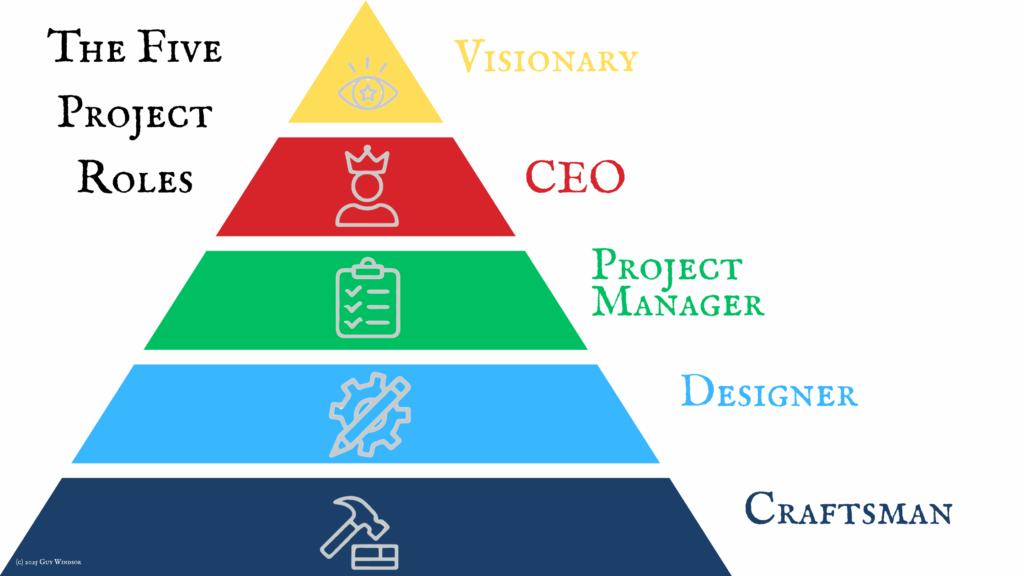

Every project, no matter its size, needs five people. Most of us have only one: ourselves.

I was chatting with a friend the other day, and he mentioned a framework that his dad, a very successful entrepreneur, came up with. According to him, the five people every company needs are: The Founder, The CEO, The Project Manager, The Engineer, and the Builder.

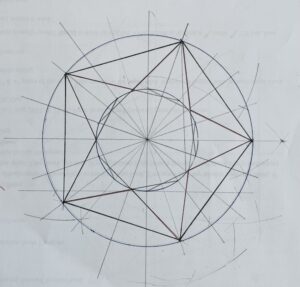

For some reason this stuck with me, to the extent that I’ve been making weird pentagonal drawings on the back of random printouts:

It's always a sign that something is brewing when I start spontaneously doing geometry. For weeks I couldn't get this idea out of my head. It explains many of the challenges I've faced running my business, and has highlighted some areas I need to work on.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Five Project Roles

The catch? In my world, and probably yours, all five roles are played by the same person. But they are very, very different roles requiring unrelated attitudes, aptitudes, and skills.

The aptitudes are:

- Vision,

- Execution,

- Management,

- Design, and

- Craftsmanship.

Very few people possess all five personalities and skillsets. I certainly don’t. But using this framework I can see why and how I’ve ended up outsourcing the things I’m not good at, and also confirmed what I absolutely must not outsource.

Case Study: The project roles you need when writing your book

Let’s take a concrete example that many folk can resonate with: writing, publishing, and marketing a book. These are separate processes, so while the visionary and CEO are hopefully leading the way, and the project manager is coordinating the three processes, it makes sense to treat them separately, as the design and craft teams are different.

When we think of “writing a book”, we tend to focus on the craftsman: the writer actually putting one word after another, like a bricklayer building a wall. But what colour bricks, in what pattern? Where should the wall be, and how high should it go? That’s up to the designer. In this case, the overall structure and content of the book. What does this book need to contain, in what order, to what depth of detail?

Most writers act as both Designer, shaping the structure, and Craftsman, laying down the words, but a developmental editor can help with design while a copy-editor polishes the craft. So you will only need to wear your writer hat to get this part done. And most writers I know identify only as writers. This is the hat they want to wear. But here's how it should go:

The Visionary has the idea. I want to create this thing. A single book, perhaps. An entire business, for another perhaps.

The CEO figures out how the vision can be made manifest in the real word. What project management, design, and craftsmanship will we need? It’s in a CEO’s nature to veer away from the vision towards the practical. So the visionary must keep an eye on things and make sure their beautiful idea doesn’t become watered down for business or other practical reasons.

Taking a step back, who decides what book, when? How does this specific project fit into the overall strategy of the business that is being an independent author? Many writers, including me, just write whatever they want, when they want, according to no plan of any kind. But most of the really successful ones have a strategy in place. This series in that genre, spread out over this timeframe, for this business goal. That’s CEO territory. My CEO quit a long time ago in frustration and disgust. But once the decision is made, the order comes down: this book, now.

The project manager steps into office. Ok, I’m going to need the following: a writer, a developmental editor, a copy editor, a layout designer, a photographer, an admin assistant to handle the publishing platform accounts, oh, and a marketing team when we’re ready.

Then the designer (or developmental editor) looks at the brief and decides what the overall structure of the book should be, and why. Some writers just start writing and see what structure emerges (‘discovery writers’); others plan things out in detail (‘outliners’). So the designer and the writer must get along pretty well, and pass the job back and forth as necessary. Unlike creating an engine or a building, you really don’t need detailed plans in place before starting work on a book if that’s not the way your brain works.

I’m a woodworker, and when I make a piece of furniture I usually start with the overall dimensions so it will fit where it’s going to go, and that’s it. No detailed drawings, no plans, no measurement. I’m a bit more structured when it comes to books (I usually sketch out the table of contents first), but I’m nothing like Saul Bellow, who famously planned his (Nobel Prize-winning) novels “down to the last flicker of an eyebrow”.

The draft emerges and goes through the necessary rounds of editing until it satisfies the project manager. Not the writer. Writers generally don’t like people messing with their words. But they are not in charge of this bit. The fight is usually between the craftsman wanting to tweak more, and the project manager who can see that the project meets spec and so should be pushed out the door.

Then it goes to layout, and the designer, writer, layout person, and editors fiddle about with the laid-out book until again the project manager signs off, and out it goes to the publishing team.

Publishing your book

Creating the book itself, the actual print files, is down to the graphic designer. Again, some writers can do this themselves, but most really can’t, or shouldn’t. Graphic design is its own thing. This, I would say, is still craftsmanship, but in a field that most writers have no knowledge of. For simple text-only books there are tools like Vellum which put simple book design within reach of the graphically unskilled, but for more complex projects (like my From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice series, or my workbooks) you absolutely need a professional.

Then who organises the planning, writing, editing, and layout, and gets the finished files uploaded to the right places, so the book is actually published? That’s project management, pure and simple. A lot of Indie authors do this for themselves too, and many stumble at this point. Because it’s hard, not least because emailing an editor to say the book is ready to be edited, or sending the edited files to the layout person, feels like handing your baby over at the daycare centre.

Then it goes to layout, and the designer, writer, layout person, and editors fiddle about with the laid-out book until again the project manager signs off. The writer, layout person, and editors, are all craftspeople, with their own areas of expertise, which often expand into design territory.

Then it goes to the admin assistant for publishing. The careful uploading of all the right files to all the right places, with metadata and all the rest, is a craft.

Marketing your book

At some point in the publication process the marketing team gets to work. Usually some time before the book is actually finished, sometimes before it’s actually started. Tragically often, after it’s already published.

The marketing team report to the project manager. What kind of campaigns should we run? Paid ads or no? Content marketing? If so what kind? The marketing approach should be engineered to fit with the vision, the overall strategy, and the project management of the book itself.

Most writers have a severely under-developed and under-staffed marketing team. The writer says “I’ll mention it on my socials” or “I’ll let my email list know” and that’s that. The question really is how does the marketing strategy fit with the overall strategic vision? If my strategic vision is “I want to write my books and don’t care how they sell”, then no marketing plan is required. If my strategic vision is “these books should pay the mortgage”, then a marketing team (usually still just another facet of the single person doing all these roles) needs to make that happen.

A common problem with marketing teams is that they mess up the vision, just like CEOs. It may be part of your vision that your work is at the luxury end of the market (super-fancy $100+ special editions), or that it’s as accessible as possible (hello free ebooks), or some combination of both. But the vision will determine the price-point, which is the starting point for the marketing. It’s easier to persuade people to buy a $10 book than a $100 book, but pricing is related to value, so you need to have a clear idea how much value your books will deliver.

My books are generally much more expensive than novels (my paperbacks go for about $30), because I’m not selling a few hours of entertainment to a broad range of people, I’m selling months or years of utility to a narrow range of highly interested people. That comes from the vision, which determines pricing. I also have premium-end books (in the $60 full-colour hardback range), and ebooks priced to be accessible for anyone who really wants the information ($10). I make about half my income from book sales: they literally feed my children. That’s both a product of the pricing strategy, and one of the reasons for it. But my marketing really needs work.

If you're looking for help writing, publishing, or marketing a book, my marketing team would lynch me if I didn't mention From Your Head to Their Hands.

How much time does each project role get?

- 80% of the work is done by the craftsman. Typing out the right words in the right order, deciding what images are needed and where they’ll go, producing the file that goes to the editor and then to layout.

- 10% is done by the designer. Organising the material, making sure the whole thing will hang together.

- 7% is project management, getting the craftsman, designer, editor, and graphic designer talking to each other.

- 2.9% is the CEO making sure the project manager is on the right track. Once the team is assembled, the CEO is really only there to keep things on track with a gentle hand on the tiller.

- 0.1% or less is the actual spark of vision. The visionary can literally be done and dusted in a second. The idea strikes, and that’s that.

Let’s put this in a Fiorean framework, just for fun (Fiore was a 14th century master of knightly combat). The Visionary is Ardimento, boldness. It takes courage to see through what is to what might be. The CEO is Avvisamento, foresight, the strategist. The Project Manager is Presteza, speed, making sure everything actually gets done on time. The Designer is Forteza, strength, which comes from structuring everything correctly. So who is the Craftsman? Every single master, remedy master, counter-remedy master, and scholar in the treatise. They are actually putting the plan in action in the real world.

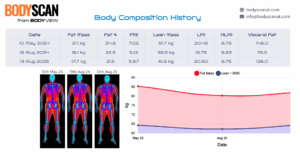

The most obvious thing I’ve noticed in my own work using this framework is that my craftsman, designer, and project manager are getting lots done. I produced six books and two online courses in 2024. This year so far I've produced four new online courses (Vadi Longsword, Vadi Dagger, Body Mechanics, and Introduction to Historical Martial Arts), and one or two more books are expected out by the end of this year. I think that counts as “lots”.

But my CEO is usually on holiday, and the visionary gets almost no time at all. Which is ironic given how this all started, with an actual vision on a Scottish mountain a quarter of a century ago.

Wearing All Five Hats as a Solo Creator

This framework matters because it is very useful for making decisions. Which of the five project roles should be to the fore, which hat should I be wearing, when I decide a book is ready to publish? Really, it should go through all five.

- Does this book come from an authentic vision?

- Does this book meet our strategy goals?

- Is this book technically ready to publish?

- Is this book well structured, so it will do its job?

- Is this book well made, in terms of writing, editing, and graphic design?

My current work in progress is From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice: the Dagger Techniques of Fiore dei Liberi. It’s with the editor now, and available to pre-order here. See? The marketing team is on the case even while the publishing team is in play. The vision is clear: this is 100% on-mission, making my interpretation of Fiore dei Liberi’s art of arms more available and completely transparent (the book includes every single dagger play in the treatise, with the image from the manuscript, my transcription of the text, my translation, my interpretation with academic justification, and a video of how I do the play in practice).

The CEO thinks it aligns with the strategy.

The project manager is keeping an eye on the editor and has the layout professional ready to go (and in communication with the editor directly).

The designer is happy with the structure and overall content.

The craftsman was sure he was done tinkering and needed a second opinion before further improvements could be made, so agreed to send it to the editor.

Phew.

I’m also working on a new facsimile project, similar to my Flower of Battle. It will have the straight, unaltered, facsimile of Philippo Vadi’s De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi, and a second facsimile with my translation superimposed, and a link on each page to a video of my interpretation of the play. It’s a lot of work, but most of it was already done for other projects. The translation comes from The Art of Sword Fighting in Earnest (with minor edits that will also result in an update to the book), the video clips come from my Vadi Longsword and Dagger courses.

The project manager was perfectly happy just using the videos as they are; all of the dagger plays are edited page by page, but the longsword plays have a video each (they are more complex to set up and explain). For this project, I really ought to create a new set of title cards, and re-edit the videos so that there’s one video per illustrated manuscript page. That’s about 56 videos.

The project manager was horrified by how much time that would take, for what is basically a cosmetic improvement.

The craftsman told him to bugger off.

Which role is not getting their fair share of my attention?

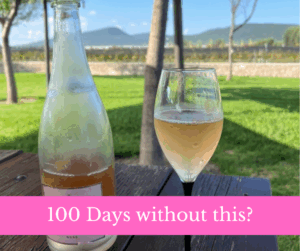

As we've seen, from the project manager on down everyone is working pretty hard. But the CEO hasn't got a lot of my attention lately. The last formal CEO thing I did was attend a business seminar with Joanna Penn and Orna Ross on The Creator Economy in 2022. And when was the last time I sat on a mountain?

To give the visionary a fighting chance (and maybe to get the CEO to return to work) I’m taking a week off from all screens and inbound traffic. No email, no socialz, no phone. Which means no actual making stuff unless it’s woodwork or bookbinding. No writing unless it’s pen on paper. No distractions. Give the inner voice a chance to be properly heard. We’ll see what comes of that. My feeling is that anyone who knows me well enough to need to contact me urgently will also be able to contact my wife and/or kids, so can find me that way. Everything else can wait a week without the sky falling.

I’ve done similar retreats before, but this one will be a bit different, as I’ll be home, and not on holiday in any way. It’s work, just of a different kind. Meditation, exercise, writing, reading, thinking. Not typing, editing, or responding to external requests for my time. That’ll run from Wednesday October 1st to Wednesday 8th because I have a regular zoom call with my mum on Wednesday mornings where we solve cryptic crosswords together, and I’m not cancelling that. But it’s all screens off the moment we hang up, until it’s time to get cracking again the following week.

The visionary’s whisper can’t be heard over the noise of constant production.

So whether you’re writing a book, starting a historical martial arts club, or building a shed, ask yourself:

- Can I hear the Visionary?

- Is the CEO guiding strategy?

- Is the Project Manager keeping things on track?

- Is the Designer building a solid plan?

- Is the Craftsman executing their art with skill?