GW: Hi, everyone, this is Guy Windsor, also known as The Sword Guy, and I’m here today with Siobhan Richardson, a martial artist and stage combatant. I first met Siobhan at the International Sword Fighting and Martial Arts Convention in Detroit many, many years ago. And we’ve been to seminars and stuff together off and on ever since. So without further ado, Siobhan, welcome to the show.

SR: Thank you, Guy. How are you today?

GW: I’m very well, can I just say I nailed that intro in one take for the first time ever, which as an actress I think you can appreciate what that’s like.

SR: Yes, absolutely. The number of times I have to do a cold reading and I’m like, wow, I hope all these words come out of my mouth properly.

GW: So let’s just orient everybody. Whereabouts in the world are you?

SR: I’m in Etobicoke, Ontario, which is on the west side of Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

GW: OK, lovely. Canada is very well represented on this podcast. So what made you want to start historical martial arts stage combat sword stuff in general?

SR: Oh, so the whole kit and caboodle. My first exposure to Western sword fighting really was when I was at school in musical theatre. We had one of our maitre d’armes of stage combat here, who is J. P. Fornier, and he came in and taught us a really basic stage swordplay for some work that we were doing. But also it’s really good for every actor to have a little bit of it. And at that point I went, “Oh, this is something I want to do.” I took to it right away, because prior to that, I started ballet when I was about four years old. I studied Chinese Kung Fu in my teens. So I had a bit of a balance of movement precision as well as the ability to use weapons. One of the things that some actors have a lot of trouble with, is integrating with the props. In fact, dancers are really amazing at taking on choreography but sometimes have a hard time with that interface between themselves and the weapon. So when I was in musical theatre school was my first time I held a stage sword. But what really brought me into historical martial arts was when we were at the Paddy Crean International Art of the Sword workshop in Banff, Alberta. That was in 2006. And that particular year there were a number of historical martial artists there. And that’s the first time that I had actually seen Western weapons being used in an accurate fashion, what really made sense to my body. What I found throughout a lot of my stage combat training, was that there was something about the choreography and the movement of the weapon that wasn’t quite making sense. I had no vocabulary to understand what it was. I know now that it has a bit to do with the biomechanics weren’t necessarily right or the techniques were being applied to a sword that it wasn’t ever meant to apply to. And our props at that time, our swords at that time were not well constructed, so the balance was off. And there’s a lot that, as a mover from age four, there’s a lot about trying to execute techniques with the wrong tool and a poorly made tool that my body just railed against. So then when we got introduced in 2006, 2007 to historical martial artists and started holding better weapons and learning more specific biomechanics and some more specific stylistic choices, that’s when this whole extraordinary world opened up to me of – the excitement and interesting – oh, I’m such a nerd for how bodies work. That was just extraordinary. And so right after that, Brad Waller was holding the Shenandoah Project which was meant to be for advanced students and for instructors and masters to work with advanced students. I was able to be a student during that. That’s when I started to learn more in-depth detail about various schools of thought. So, yeah, that’s how that that’s how it all got started.

GW: So what are your preferred weapon styles?

SR: I have a few. I love smallsword. I grew up doing ballet, so smallsword fits into my body in a way that makes a lot of sense for me. I also love longsword.

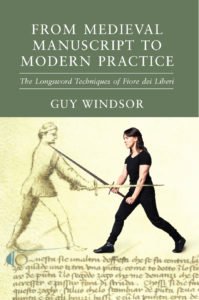

GW: I should hope so. Actually it could be that the listeners haven’t quite twigged to this, but you appear holding a longsword on the cover of my new book

SR: I’m absolutely thrilled, I’m so honoured. It’s such a lovely picture. I’m very, very proud. I love it. And I love longsword for the same reason I love smallsword. There is something about the way that a longsword works with the whole body that makes sense to my dancer brain. And it’s not that other weapons don’t, but there’s just something about the way the longsword moves with me, I suppose it’s some bloodline far back or something that just genetically expresses itself. But I also enjoy some of those theatrical cloak styles that we do. So it’s one of the stylistic differences between historical martial arts and performance of martial art.

GW: What’s a theatrical cloak style?

SR: Whereas in historical martial arts, the cloak is like, sometimes you throw it, sometimes you flare it, wrap around your arm and use it as an offhand weapon. On stage we do a little bit more in the way of, you could even just call it posturing. But we do a little bit more in the way of flaring the cloaks that we see a lot of pictures. The audience gets a lot of movement to look at. So then in choreography, we tend to use that flaring action and then perhaps finish it off with a parry at the end of it or part of that flare. We emphasise the distraction technique of the cloak. So that we tease out the parts that maybe if you’re fighting for your life, you wouldn’t do quite as much of. But when we’re portraying a story of someone fighting for their lives, but we want to keep the audience’s interest and we want to help them be inside of that story in a way of having enough time for their brains to catch up on what’s happening. So some of that expansion we can do with cloak really easily because the time of the cloak is the time of the cloak, whereas with various other hard weapons, there are some things that we do on stage to shorten time and expand time. It’s easier to do because the weapon is rigid as opposed in cloak you are a little bit more forced to hold to a longer time sometimes, which is handy when you’re trying to get actors to engage in a particular way.

GW: OK. So, yeah, the movement of the cloak, once the cloak starts moving it you can’t stop it until it’s done.

SR: Exactly. You can’t push it through the air faster. And that’s actually like one of the basic mistakes people tend to make is they want to push the cloak through the air. No, no, no, no. You just you suggest a direction and let it do its work.

GW: You mentioned something about the connection between ballet and smallsword. I think I know what you mean, but I’m fairly sure that many of my listeners might not. So do you want to expand on that a little bit?

SR: Sure. So the ballet, as we know it now, is not what it was in its origins. Its origins was baroque dance. So the shapes are very different. But some of the extension, oh, my goodness, the extension that people have now, where they’re going like over 180 degrees is just astounding. Whereas the original moving of that form, it was a little bit more like ornamented walking. But that particular dance style was codified at the same time that smallsword was codified in the French court of Louis XIV. So some of the terminology is very similar. Some of the weight distribution is similar in some of the further study I’ve done in

smallsword. Even some of the some of the basic training, the beginnings of training, are done in a very similar fashion. So I find that with a ballet, even a contemporary ballet, vocabulary in my body, there’s somethings about the weight distribution and how your legs work and how your feet work in smallsword that make a lot of sense to me. Also, like deportment, the way we organise our limbs in ballet is actually quite similar in some fashions to swordplay.

GW: I had a student coming to one of my smallsword classes some years ago whose core art was ballet. And she came up to me afterwards and said, “Guy, do you do ballet?” I have never had a ballet lesson in my life. Well, it makes sense because, you know, in the 18th century, dance teachers and sword teachers were often the same person.

SR: Well, of course, because they were complementary art forms. I mean, even down to the way you tilt your head, I guess that might be a school of thought thing. But when your hand is in front of you, rather than keeping your head square, sometimes you tilt it to an angle just to make sure it’s really protected behind your guard. And we very much use some of those same lines because they’re aesthetically pleasing. So that’s where if you ever watch the, I forget what it’s called now, but in Swan Lake there is the dance where there’s four women dancing and the head tilts are even choreographed as part of the quick movement, which is sort of a further specialised expression of that tilting of the head to keep it guarded, but also the beautiful aesthetic line that you create when everything’s in alignment.

GW: Fascinating. Clearly, you do lots of things and you obviously are deeply interested in all of them. So what does your training actually look like?

SR: I have always been very interested in the longevity of the body. Starting as a ballet dancer there’s always that impending threat of once you hit 30, your career is done.

GW: At 40 it’s hip replacements.

SR: Yes, exactly. So I’ve always been very interested in preventative action. So a lot of my workouts and a lot my warm up has to do with making sure my feet are working well, making sure the sequencing is correct. I’ve got my Therabands and I do a bunch of physio exercises. I also use Indian pins [clubs] do that kind of warming up of the joints. And again, making sure everything is working cohesively. So my workouts tend to start to get my body working just as the machine it is, and then for the specialising into whatever I care to work on that day. It’s a lot of working basics. And for me this comes out of my ballet training. Every ballet class starts with basic foot warm ups, Pliés, just bending your knees and straightening them, just extending the foot and bringing back and then scaling up with that. So I find that my personal training tends to follow that same kind of patterning. So I’ll start general, and then I’ll specify into what I want to work on that day. Lately it’s been a lot of longsword. And actually, in sword and buckler, I’ve been doing a lot more. So speaking of the quality of the instruments, as the years have gone on, I have acquired better and better pieces, better and better weapons. And one of my most recent prized acquisitions is a second hand sidesword. So I have been just loving how it feels. My forearms feel great. My wrists feel good. And that that interface between the hands and the grip, that’s one of the things I learnt from you, was this this idea of making sure you’re actually communicating with the weapon through the grip and how that interface means…

GW: Connecting your ground path to the edge.

SR: I enjoy doing a lot of that. I’m also one of the very lucky people who has a partner who is also working the same art forms. So there’s a lot of partner drills we can do on an almost daily basis.

GW: Despite lockdown.

SR: Actually more so because of lockdown because before this I had been doing so much travelling with work. It hit me the other day. I haven’t been home for this length of time for years. You do a ton of travelling too.

So I’ll do some basic movement stuff, but I’m doing a lot more in the way of cardio and strength training as well. I’m happier when I do it. And it amazes me – one day it really hit me just how much that cross training is so, so key to improving your art form because everything’s working well, you don’t have to spend your craft time working on those foundations in the same way.

GW: Right. I’ve lost count the number of times student, not a terribly experienced student, would come up to me and say, “Guy, when we come to class in the evening, you’re there doing your own training before class and we almost never see you holding a sword. Why is that?” And I’m like, well, the sword is just the tip attached to the spear. It’s just that last little bit. Or it’s the drill bit you put into your drill. Ninety five percent of my training is making sure that, when I attach a sword to my body, everything is going to work properly.

SR: Exactly. And I think that’s one of the things that I wish more actors understood, because when I come in to choreograph, I am an actor, fighter, singer, dancer or a performer first. But I’m also a fight choreographer. So I teach other actors how to do things and arrange for stage productions. And that’s that idea of making sure the core of the instrument works better. I wish I had something that more actors really understood, because sometimes when we go in and do choreography, I mean rightly, they want to get the choreography correct, they don’t want to hurt the partner, but they’re really focussed on the weapon and on the choreography and they don’t necessarily understand the part of it that needs to be the weapon as an expression of their intent.

GW: Right. But it takes it takes time for your nervous system to basically incorporate the sword as part of itself. They have done these brain studies. Like for an experienced carpenter, their brain experiences their hammer as an as literally as part of their body.

SR: I tell my students that all the time.

GW: You can always tell an actor who doesn’t really connect to the sword properly because when they’re moving around on stage or on screen it’s like they’re trying to do the moves of an experienced swordfighter but you don’t believe it because they are clearly not.

SR: It always just looks like two props in the air moving at each other. I love that moment when I see a couple of performers who, or a performer, who really understands it. Because I then notice, as an audience member, I am watching them and their experience in the moment. I’m watching that character. I have an experience as opposed to watching a couple of props moving back and forth at each other. I call it the Michael Bay of stage work because it’s like shaky cam – I’m just watching things happening and I’m feeling stress, but I’m not experiencing a story.

GW: Now we all have things we know we ought to be doing more of. Is there anything that you’re neglecting from your own training?

SR: Very personally, I need to do a little bit more work on my foot strength. I have nine ankle sprains, distributed three on one, six on the other.

GW: That’s not good How did you get those?

SR: Well, the first one was playing volleyball. Then I was 14 just when I was getting en pointe, so just the psychological devastation of like, “Oh I’ll never dance again!” I did. I’m fine. But then subsequently one of them was performing a stage combat demonstration with someone who didn’t know what they were doing and they genuinely twisted when they shouldn’t have. And then I had two sprained at once at one point. I was rehearsing for a show and one went and then the other. So I was walking on the slightly less sprained one. I’m trying to try to sit here and elevate one foot and then try to move myself to this side of the room on my on my ball chair. It was not ideal.

GW: Okay, so you should be working on basically rehab for your ankles and feet.

SR: Yeah. Just a little bit more detail. I had been doing a lot of focus on my ankles and calves. But I knew I had a gig coming up that was teaching theatrical martial arts in Europe. So I was teaching essentially Eastern martial arts unarmed for stage fighters. I knew that I love jumping. It’s one of the things that I always aim towards. I just I love being airborne. And when my ankles aren’t doing well there’s quite a bit of fear attached to that. So I went to physio to say, look, I don’t want to be afraid of this anymore. And I want to get beyond just kind of the repair work. How do we how do we really make me strong? And at that point, it was pointed out to me that it’s a little bit about the ankles, but it’s also actually about the way my pelvis was working. So my glutes weren’t firing enough, so there wasn’t enough pelvic stability. So the ankles are trying to take over for it, right? The last full month or so has been more intensely working that pelvic carriage, really getting the glutes going. So now I’m just noticing that my ankles have some catch up work to do.

GW: Interesting. OK. Do you have a particular person whose work you follow in terms of foot strength?

SR: Oh, I quite like the Franklin method. It. Are you aware of it?

GW: I’ve read up a little bit about it. I’ve not done it.

SR: He has a particular Happy Foot book and balls of a particular density full of air. But you use them for a lot of stuff that a lot of people who’ve investigated foot strength are aware of. Things like doing gripping with the foot and working the flexibility and the strength of the foot. Why I bought the book is I like having a bit of a thing to follow. So that book gave me a little bit of a path to follow, as well as the balancing aspect. So by balancing on these inflated balls, it forces the foot to work a bit differently. So it makes things work and then using a theraband around the toes to get to work. The gripping through the toes. So I quite like the Franklin method for that in particular. And there is another programme I can’t remember, which was a very long time ago now, but encompasses a little bit more in the way of foot massage and releasing some of the tension that gets in our feet from when we wear really blocky shoes all day.

GW: I don’t. I’m a barefoot shoes person.

SR: I am too now, for sure. I was at a military surplus store and I found the minimalist military boots and I was wearing those for years and mine finally died. I love them, but they’re not making them anymore. So I need new winter boots – keeping my eye out for those. But I’m very happy now that we are quite firmly in summer and I can pull out the whole barefoot shoe wardrobe of which I have several. And I went on the website, got some pretty swanky saddle shoe leather, barefoot shoes. They’re very lovely. I feel pretty swanky when I wear them.

GW: Good. Just in case you hadn’t come across her, are you familiar with Katie Bowman? You might find that she has fantastic stuff on biomechanics and she has some really interesting stuff, quite approachable foot exercises, which I’ve used. The interesting thing about buying her book was it’s obviously aimed at women and tried to persuade them not to wear high heels anymore. I’ve never been a high heel kind of guy anyway.

SR: Not even when you’re doing smallsword?

GW: Well, maybe doing smallsword. But it’s not the heels I do smallsword for. I’m more of a kind of handmade brogues kind of a chap. But they don’t make those barefoot either. You can’t get a really good proper marriage between a barefoot shoe and a handmade brogue style.

SR: We were at a farmer’s market in Calgary, Alberta. And for people who are not really aware of Canada, that’s where the cowboys are. So good leather. And we found a guy there that was making handmade shoes. So that’s one of my dreams. My husband got some handmade shoes. I would dearly love to invest in for myself a custom-made pair of shoes. That’s on the bucket list. I seem to remember you’ve got quite an interest in shoes.

GW: Well I have. I actually go shoe shopping to relax. When I was in Melbourne my host, Scott Nimmo, lovely chap, understood me very well and took me to Rocko’s. This is before it closed, which is handmade Italian shoes made to measure but like two hundred dollars, as opposed to 2,000 dollars.

SR: That makes no sense.

GW: Yes, exactly. So it’s no wonder they went out of business. I have this lovely pair of two tone brown and cream. All these shoes, they have heels, and I can’t justify the mechanics of a heel. It’s like smoking a cigar, it’s heaven, but it’s for very occasional, it’s unhealthy but you do it anyway because you love it, as opposed to everyday. So every day I’m barefoot or barefoot style all the time because there’s just no good argument against it. But you know, I do have my nice collection. Put it this way, I have more shoes than my wife.

SR: Do you get all the questions? I get all the different questions of like, isn’t it weird having things between your toes?

GW: Well, okay. I avoided the Five Fingers shoes for a long time. I got into barefoot through mediæval shoes. I was in Verona attending games, visiting some friends who were coming over from the States to take part in the tournament of the White Swan in Verona. So I thought, what a great excuse. We managed to find a babysitter to take the children and my wife and I went to Verona for days. It was heaven. And I realised I hadn’t used my mediaeval shoes for ages and I was going to have to wear them all day in mediaeval gear at the at the event because they’re very keen that no one goes into the reenactment area if they’re not dressed properly. So I brought my mediaeval gear. So on the streets of Verona that on the Saturday night, I thought I better just make sure the shoes work. And I went out and I’d had them for ages. They were worn super thin and super flexible. It was like I turned into a cat and it was not the slightest bit slippery. Not the slightest bit uncomfortable. It was just glorious. And so then after that, I just didn’t wear any other shoes except these mediaeval shoes. And of course, I wore through the soles in minutes. So then I got a new mediæval shoes and then I looked into the barefoot stuff. And then eventually in a shop in Edinburgh, I thought, you know what, I just have to try these things on. So I went in and I tried on a pair of the five finger things and, you know, the mediaeval shoes turned me into a cat. These turned me into Spider-Man. I just kept jumping on rocks walking through the park in Edinburgh. I just jumped onto things because you can. They’re fantastic. The only reason I don’t wear them more often because you have to wash them every day or they stink really quickly. And because my feet are very narrow the toe socks that you can wear with them don’t ever fit my feet properly. Because basically you get almost like a straight line of toes and I need them closer together and more shaped so the little toe is much further back on the foot than the big toe. And so they just don’t fit the socks don’t fit properly. So I can’t wear the shoes with socks. I just realised that no one tunes into this show to listen to me, they are here to listen to my guest and here I am rabbiting on about toe shoes.

SR: I’m fascinated! Here is a quick thing about shoes. My Instagram feed is of course full of ballet stuff is as well as all the other stuff I do actually. So it’s talking about pointe shoes. And as you can guess, pointe shoes need to be very specifically fitted. If any of your listeners have not ever gone into a pointe shoe store, you would be as astounded at the at the range of sizes and styles, but it was talking very specifically about like essentially your toe organisation and I guess common “arrangements”, I suppose you could call it. I wonder if and when some barefoot sock specialist will jump on that. I feel like it’s a little bit niche at the momement. I know a bunch of people would try it but it’s the wrong shape for my foot. So it’s always weird because my toe is never actually in the toehouse.

GW: Seeing as we’re talking about shoes and equipment. Now, equipment is a big thing in swordsmanship. Obviously, the weapons, the protective gear. I imagine in stage combat, you tend not to use so much in the way of protective equipment. But what is it like equipment wise? How do you feel about masks and gauntlets? And if you have an equipment rant now’s the time to unleash it.

SR: Oh, breast protectors. I haven’t been doing as much martial arts at conventions and such lately. It’s been more on my own studies. When we do it for stage, we don’t tend to have protection while we’re on stage. So I don’t interact with them as much. But last time I was looking for a protector they came in two sizes, small and big. And that’s completely inaccurate to the various kinds of torsos that are out there. So there was a time when I was seeing a lot of ads for custom made protectors, and I’d love to get on that. I just need them. So next thing, gorgets – the first time I went to a tournament and saw a point slip under the bib. As a singer, I was terrified. Holy shit.

GW: As a human being, you need to breathe. Whether you’re a singer or not. Crushing the airway is not good.

SR: As we were preparing for this, we talked a little bit about like the differences between studying swordsmanship for performance and studying swordsmanship for self-defence and as a craft of its own. And one of the one of the things that I’m always aware of as someone who designs violence for stage is the psychological effects. As we go. So when we’re putting things together for stage, it’s not only about what’s the ideal my character is trying to achieve, but also like what is happening in that situation and how does that affect me psychologically? And while in martial arts, our aim is to release that and focus on the moment, in storytelling it’s actually a really essential element for us to think of what are the psychological effects of what’s happening. And I think it was Philip Dorlean who first really pointed this out to me: to break the fingers of a runner is not the same thing as breaking the fingers of a piano player. I bring that up because of that, of course, as a human being you need to be able to breathe, but that moment of oh, the terror. And that’s what happened when I first sprained my ankle that moment of “I will never dance again” or that moment of, “What if something happens to my voice?”

GW: Are there good gorgets out there? Do you have a preferred?

SR: I don’t. Because in my training, I tend to stop short of actually going into tournaments. I haven’t gone down the rabbit hole. But something that I could rant about is swords and what’s being made well and what isn’t being made well. And the absolute delight of finally having items, having weapons that are better and better balanced, seemingly everyday. When I first started, my first contact with stage combat weapons and sort of martial arts weapons, and I didn’t have the vocabulary at the time, was just how poorly weighted they are, the really old ones. We keep a couple around now to show people why they did it like that is because this was the inaccurate equipment they were working with and oh man, just a steel rod with a handle on it.

GW: I’ve actually handled historical original swords that handled like a steel rod. Horrible. And others that just they just magically attach themselves to your hand and the point just effortlessly goes where you wanted to go before you even know you wanted to go there.

SR: Yes. So that’s more the experience I’ve had.

GW: Most people who are handing out the weapons to handle will give you the nice ones.

SR: Yeah, exactly. Well, in 2009 I got a Chalmers Arts Fellowship from the Ontario Arts Council. So that was a grant that allowed me to travel around the world a little bit and study various martial arts and especially with particular application to performance. And during that, I went to Leeds and I went to the Wallace collection. Wonderful places to go when you’re in London or in the near area. And had several hours of being able to handle pieces. And that was I think that was the first time I actually got to handle historical pieces. And of course, the curator is going to give you the absolute best versions. My body sang. It was kind of a transcendent moment.

GW: It’s one of those things when people ask me, “Why do you do swords?” I know I’m talking to somebody who will never understand it. Because what you just said about you pick up the sword and your body just singing, yeah, that’s how sword people are. And I think it’s intrinsic. I mean, for some people it’s like they either they get behind the wheel of a Maserati and it’s probably the same for them. I don’t know, because, you know, I drive a Nissan Micra because I care about swords, I don’t really care about cars. But I think for us sword people. That’s the defining feature. We are drawn to that.

SR: And I think that’s what I experienced even in that first stage combat lesson was there’s something that there was something already going, “This makes sense”. I’d done some weapon work in my Kung Fu years. And I always sort of put it up, to, well, I had an experience with it from before, but not till this conversation. I went, no, there’s just also something in me where this movement makes sense. Like I wouldn’t call myself a violent person. Like, I don’t go around beating people, but I love martial arts and I love the physical expression and I love that interplay. It’s one of the reasons I do it is that the intensity of that communication and from an actor’s perspective, that moment of us being in perfect communication with each other and perfectly present to what’s happening. It’s about being perfectly present and not about perfect repetition. When some people aren’t doing stage combat well, it looks great, but there’s something missing. It’s because they’re repeating it perfectly by rote. As opposed to really being present to the moment and just the little changes that happen in the moment.

GW: It’s the essence of live performance.

SR: Yes, exactly. So to lock it into like “this is the perfect repetition” is antithetical. And then my proudest martial arts moment is when I find that, but with the “I don’t care about you” part of it. So here’s the thing, when I go from performance to martial arts – in performance I am deeply invested in taking care of you. I am deeply invested in putting this where you need it. In giving you a cue so that you know, you remember where the next thing is. And I cue your body to go “you’re supposed to go here”. And that’s something that I do when I’m performing is I make sure that I know my partner’s choreography because I need to make sure I’m cueing them subconsciously. Whereas when I’m then looking to work my martial arts, I do less caring about putting this where you need it. I actually have to shift my mindset from intent.

GW: I had the same thing with dance. Many years ago I was, I was single for a short while and I thought I’ll go take a tango class because I’ve always liked tango and you know, I’ll probably meet women there. That’ll be great. And I did meet women there, but they tended to be sort of in their 50s and not available. And anyway, I was like 30 at the time. So I just kept going because I actually like the tango. Oh, this is great. And I could pick up the choreography quite quickly because I’ve got a martial arts background. I’ve got forms and stuff. The teacher said, “you’ve never done this before?” No. “But you remember that thing we did from last week.” You mean this one? I practise at home. “You practise at home?” Yeah. But anyway, there was this key moment when you know, because tango’s got lots of dips and twizzles and, you know, basically the man tends to be directing the women around and doing lots of lots of listening and replying. And I’ve done martial arts and I’ve done riding. And I realised that tango, although you’re holding a person in your arms, is much more like riding a horse than it is like wrestling. I didn’t actually have to put the person into the position. I simply had to give the lead, the signal. And they would then do it. And when I cracked that I became a lot more popular with the ladies because I wasn’t throwing around anymore!

SR: That’s awesome. I enjoyed that very much. Oh man. I do love wrestling. I do love being thrown around a little bit. But I can see how if I’m in my high heels and looking for a social dance…

GW: It looks like you’re doing a hip throw but you’re really not.

SR: No, you’re suggesting a movement.

GW: Exactly. It took me maybe two classes to figure that out. When I reckoned it’s riding, not wrestling. Then everything went a lot better.

SR: The gentlemanly arts.

GW: It’s that communication. Stage combat, tango whatever are fundamentally co-operative. And a martial arts contest is fundamentally noncooperative. For while the movement may be identical, the intention behind it could be different.

SR: I’ve had a few moments where I’m like, “Oh, that’s what that is.” That was one of those moments where I went, oh, I get it now. And another one of those like something in my body and something in my brain that just made sense. And I had one day that I just kept hitting people. And I went, “Where am I? What did I do?” Because of course before that I was being hit incessantly because I was a learner and I was new. So that was one of those days. I just figured out these two things work and I’m going to do that and I don’t care where you are, I’m going to put this in your way and you’re going to happen to walk onto it. I’m to move my arm like this and if you happen to walk into it, it’s not my fault.

GW: That that that doesn’t fly in a stage combat class.

SR: No, no. Speaking of antithetical. So in a stage combat class it is so much about accuracy and precision, but also ease and receptiveness. A lot of people try to get their accuracy and precision by forcing something into a spot. But that’s when they’re not listening so they’re not able to respond to their scene partner. It shouldn’t be an advanced skill, but it seems like that becomes an advanced skill because if someone is coming at you and they’re not quite sure what they’re doing or they’re moving only in their own pace, you end up doing a lot of, “OK, I know I have to abandon that early in order to find this,” and coach you into the next bit or move with you into the next moment. Something I’ve learnt about teaching stage combat, so essentially teaching martial arts as a collaborative form is how much it is about those foundations, like the mindset. Some people focus only on what body shapes they’re making and also just the positions I’m hitting. When you’re talking to actors and engaging what that thought process is and what is the kind of listening they’re meant to be doing and so engaging those skills they already have of blocking and countering, which in a stage perspective is how are you balancing the visual picture of who is spread out where on the stage and how are you responding in physical space to each other on a grander scale and helping them understand that we’re now doing that but in the two metres between us. So, yeah, so much about the mindset where what people focus on the physicality only.

GW: Yeah. Because that’s the obvious thing.

SR: Yeah. And that’s what you sort of you think it is, if you haven’t done it. I don’t know. I won’t pretend to guess what the reason is. But, yeah, without that inner substance, it’s also just not the essence of performance. We go to performance to see truth. And truth might not be realistic, but we’re looking for the truth of that experience. I’ve always thought of performance as allowing the audience to live vicariously. So we have to present it to them in a way that they can actually live with it, as opposed to showing them a thing or doing something for ourselves.

GW: It’s exactly the same when teaching a class. Because if I’m demonstrating a technique in front of the class, nobody else in the room will do that technique exactly the way I do it, because they are different heights, their pelvis is a different shape, they have a slightly shorter sword or longer sword or whatever, and they’re not me. But if I can show them the feeling of the movement, and they can pick up what it should feel like when it’s right. Then when they do it, it looks beautiful. And you can pretty much always tell a beginner because they’re trying to remember the technical sequence that they’ve just seen. And the more experienced students are just absorbing the whole thing that they’re looking at. It’s like learning a language. When you first learn a foreign language and somebody is speaking to you in that language, you get one word and translate it, and the next one and translate it, and the next word and translate it. And then you look at those three words together and you go, “Now what does that mean as a whole thing?” But when you are familiar with the language then that phrase you’re absorbing is a whole phrase and the nuance of it and the connotations of it and the tone of voice in which it’s said, all that sort of stuff, you’re absorbing the feeling of it.

SR: I love that you’ve said that. During my Chalmers Arts Fellowship that was kind of the point that I was trying to understand. I knew that there was something to that idea of movement as language. Then when I did that study, that’s when it finally made sense to me. The idea of swordplay movement really is about learning a language. You’re learning a physical language. And so that’s a language I use when I’m fight directing to help actors understand that it’s not about the individual moves. It is so much about the intent and about the response that the audience perceives. Just like it’s not really about the words that you say. Of course, if you’ve got beautiful words and you’ve got well-crafted words with great grammar and in a good order (that’s a fantastic phrase), then what you’re experiencing is going to be of a different level than if the text is not so well written. Similarly, if your choreography doesn’t make sense, your likelihood of giving an amazing show is not as high as when the choreography is excellent and well expressed and suited to the actual performer. But in the end, it isn’t actually about how awesome the moves are, it’s about how well they’re expressed. Unless you are doing thirty two fuettes, if you are doing an amazing move because it’s an amazing move, you have to recognise that you’re doing that as a virtuoso, like check out this instrument, check out this expression.

GW: It’s like a cadenza at the end.

SR: Absolutely. But it is so much about the experience.

GW: OK. We could talk all day. All right. Let me just really start bringing this gently to a close as I’m sure the listeners have things they need to get on with, like, you know, looking after children and working for a living and stuff. So I have a couple of questions I’d like to finish on. The first is, what is the best idea you’ve never acted on?

SR: I feel like I have a lot of them. Well, you did prep me for this question, but I now I’m like, oh, what was it?

GW: You have to have anything, it’s just most people do. Some people have a book they should be writing, or for other people it was a specific policy they should have followed up on in their school. And they’re now going to go and apply that policy because it’s going to make the school better. Or we all have these ideas that we know we if we just went on and did them, things would be good.

SR: Yeah, I have a couple of them, I think, because of the way my life has been able to work out there’s a lot of great ideas I’ve had that I have actually acted on. So I have very few in the way of that thing I missed. And I’m actually in the midst of one right now where I’m like, “Oh, I’m doing this thing.”

GW: What’s the thing?

SR: So if your listeners are aware of what’s happening in theatre and the Me Too movement and such, you might be aware of this new thing called Intimacy Direction, where we choreograph scenes of intimacy as opposed to just letting people improv it.

GW: Is that what they were doing before?

SR: Yeah.

GW: Oh my God.

SR: I guess you didn’t know that. Rarely were they choreographed.

GW: I’m not an actor.

SR: So you just sort of watch and go, “Oh, a thing is happening, I guess they do that like they do anything else.”

GW: I always assumed that they were very carefully directed.

SR: No, some of them were. This is not to say that everyone’s always been doing it improvised. But some of it was choreographed. A lot of it was, “Here’s some space. Now try the thing out.”

GW: That’s freaky.

SR: Oh, that’s a whole other rabbit hole. But what’s happening now is the understanding that it should be choreographed and there should be parameters set in place, and it is the industry understanding. So that’s been that’s been what I’ve been doing for the last couple of years. Along with that, to me, includes this idea of respectful workplaces in the arts industry. There is a lot in the way of power dynamics, a lot of people doing work that maybe they’re not entirely comfortable with, but they want to work so they do it and they challenge themselves. And some people get traumatised by the work that they’ve been asked to do. Some people have been unable to find a level of challenge that is useful for them. So along with the rise in intimacy direction and the understanding that our workplaces need to have certain agreements in place so that everyone is confident to do the best work they can do. I’m paraphrasing a Canadian director, Peter Hinton, but he says a rehearsal or our workspaces need to be a safe place so dangerous things can happen. Otherwise they’re a dangerous place where only safe things happen. And that idea of what is a safe workspace is deeply partnered with the intimacy work because it’s very difficult to be as vulnerable as performing scenes of sex and sexuality if you are not confident that your workplace is one that supports you. So that’s what I’ve been doing a lot of work on as well, is not only helping the world to understand the specificity of what is intimacy direction and intimacy coordination, but also how that dovetails and where that Venn diagram crosses with respectful workplaces. And some of it is as seemingly simple, as simple to say as having conversations, to be able to say to somebody, “Oh, that was a little uncomfortable,” or, “No, that’s a boundary for me. You can’t touch me there, but you can touch me here.” Be able to have those kinds of really specific but important conversations. And some of it goes as far as what do we do when there’s like a conflict. And for me, it’s one of the bees in my bonnet of how do we spend time and space together in a way that is respectful and joyful, so we are inclusive of everybody in the room. I’m never looking to put a cap on the fun. It is absolutely about still having fun. But it’s also being able to have a conversation if you’re like, “Oh, that that didn’t work.”

GW: But without safety rules in place, you can’t have a sword fight with your friends.

SR: Exactly, yeah.

GW: So, yeah, I mean, it’s the rules that create the safe space in which the fun can happen. The rules don’t stop the fun. The rules create the space in which the fun will occur.

SR: Right. When we know where the fences are we know where we can run around. If there’s no fences, we’re don’t know if we’re running towards a cliff or not. So, yeah, so we’ve done it with in some ways we’ve dealt with physical work or we haven’t. But where in some ways a new thing is empowering everybody to be able to have a conversation, if it’s like, oh, that’s like a that’s a mental health barrier for me or the boundary for me or that’s a conversational boundary. That’s a language boundary because you’re using language that I don’t know if you understand the origin of that. But let me give you an offer for another word or terminology instead of that one you’ve used, which is actually kind of deeply offensive. But as far as other big ideas, I enjoy sewing and there’s part of me that goes like I could have gone a lot further with my cloak sewing business.

GW: You had a cloak sewing business?

SR: Yes, I still do it. It started with cloaks for stage because I was finding, speaking of equipment that wasn’t accurate, I was finding it was ridiculously difficult to find cloaks to fight with. And I went, oh why don’t I just make one? So I started making them and selling them at stage combat conventions. And I’ve actually brought a couple to martial arts conventions. You make them definitely for stage and for martial arts. Dimensions are different, the amount of weight you need on them. Martial arts, they tend to be heavier. So I tend to like to use more velvets and heavy materials. Whereas for stage, I tend to use something closer to canvas. It’s a little bit lighter, but still catches the air. So we get the flare that we’re looking for. Because for stage, we’re moving it around in the air a lot more, as opposed to martial arts, where it’s less about flying around the air and more about stopping a blow.

GW: Right. Interesting. OK. So that’s so that’s two interesting ideas that you’ve actually acted on. I think you’ve answered the question that everybody’s satisfaction.

SR: Oh, and a book. I’m also someone who’s, like, should wrote that book. I should’ve done that podcast.

GW: What books should you have you written?

SR: Oh, there’s like five of them. It’s ridiculous. The Actor’s Guide to Stage Combat. There’s a lot of how to teach it, how to fight direct it and very little in the way of actors.

GW: Yes. Interesting. Yeah.

SR: So all of that like prep that I do for myself and my own perspective on how to my act these scenes is included in that. I’ve got the outline I just had to sit on and gift myself the time to write it. And I know, Guy, I know you’ve got lots of words on this because I’ve also read your collected works on getting things done. Just for people who don’t know, you should read that thing.

GW: I will not say a word. I’m just going to trust that should you ever need any assistance, you’ll be sensible enough to get in touch immediately.

SR: I would. Yes, absolutely.

GW: Good. OK. All right. But you know, the absolute worst thing you could do to a writer is pressure them to write the next book. Should you ever decide that that’s the thing you want to do, then I’m sure everyone listening will be going like, “Oh, I’d like to read that,” even if they’re not an actor. All right. So last question. Somebody gives you a big chunk of money – a million dollars, million pounds, something like that, to spend improving historical martial arts worldwide. What would you do?

SR: I would make excellent equipment available to everybody at a reasonable price.

GW: Such as?

SR: I would make some of the foundation body work, like to prepare your own body, available to everybody. So we can get people started off on a better foot. So we have fewer shoulder injuries and fewer neck injuries that are caused by virtue of just having bad alignment.

GW: How would you do that? How would the money help you do that?

SR: Putting education out there and also getting paid for the work I’m doing as a career artist. There’s a lot of great stuff I can do. I just like to be able to eat at the same time.

GW: What, do you mean exposure isn’t sufficient?

SR: You know, like, hello Visa, can I pay my bill with exposure? I can’t? However, I mean, that’s when we get into business practises. I’m sure you and I could have a long conversation about entrepreneurship and using a “freemium” model. Good production values and the research to get it to the right people would be part of how the money would help with that as well. Getting it in front of people, also giving people the tools. So I don’t want to come across as simple, but there are many people out there who don’t have accessibility to stuff they want to do because maybe they don’t have the time and they literally don’t have the money. Maybe they are eating peanut butter all week. And if this is some little thing you can do to alleviate that – amazing. I mean, assessments. I would love to give everybody a session with a physiotherapist so that they can have a professional look at their bodies and say, here are some little adjustments you could make in your body that will help it work better. I love the idea of people being able to move until the day they die for whatever reason that is. But for one’s body to be functional, that’s my mortality issue. I just want to be able to move.

GW: Most of my private students, on the first time they come to me for a lesson, we almost invariably end up spending an hour getting them just to walk properly. So their knees stop hurting so they can then do the thing. Bad mechanics is the curse of modern life I think.

SR: Right. It’s like picking up a trumpet that doesn’t work and trying to make it make music. Make sure the valves are oiled and then you’re going to sound amazing.

GW: I actually do play the trumpet a little bit and no, I don’t sound amazing. Oiling the valves isn’t always enough. It’s certainly a good start. Thank you Siobhan. It’s been a lovely conversation. And is there anywhere you would like the listeners to go find you on the Internet? Any last words?

SR: So you can find me on Instagram @fighteractress and my web is http://www.siobhanrichardson.com/. Those are the easiest places to find me. And then from there, if you need to get in touch with me directly, you can direct message me on Instagram and you can find my contact info on my website. And if you want to see me move around, I’m on YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/user/ActorSR and you can see a couple of videos and my demo reels up there.

GW: Brilliant. Thank you very much.

SR: Thank you, guy. Thanks for hanging out. It’s great.

I hope you enjoyed my conversation today with Siobhan Richardson. Remember to go along to www.guywindsor.net/podcast-2 for the episode show notes and for a free copy of Sword Fighting for Writers, Game Designers and Martial Artists. Tune in next week when I’ll be talking to Tomas Suazo about travelling through Europe, making armour, things like that. Subscribe to this podcast wherever you get your podcasts from to make sure you don’t miss that episode. See you next week.